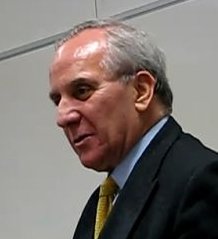

Osman Streater, who died on November 22, might have seemed to be simply the ultimate London gentleman, a Chairman of a London Club, a leading figure in City PR, an amusing but always well-informed conversationalist, and unfailingly polite and courteous, with his ironic sense of humour kept just a little below the surface.

But he was also man with a hinterland of sharp cultural and historical paradoxes. The Streaters were a British family which had settled in Turkey since the early 19th century and whose name crops up many times in late Ottoman history. His father, Jasper Streater, was a banker who met his mother, the literary critic and historian Nermin Menemencioglu, during World War II. They had married in Cairo at a time when such marriages were still considered rather daring. Religion was not a factor. Osman's maternal grandmother was Katerina, an Istanbul Greek who remained Christian until her death in the 1980s, her new family being firmly convinced that contrary to Turkish custom she should not change her religion.

Nermin's uncle was Numan Menemencioğlu, foreign minister of Turkey and a good friend of Monsignor Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, with whom the family remained in contact over many years. Her brother, Turgut Menemencioğlu, was Turkish ambassador to London in the 1970s. Nermin herself, despite her patrician background, had been one of the first generation of Republic leftists, a friend of Nazim Hikmet, Behice Boran, Niyazi Berkez, Muzaffer Serif and Azra Erhat – a generation swept into near oblivion in the second half of the 1940s. Osman, inheriting the conservative instincts of his father's side of the family, sidestepped this part of his mother's heritage,.

The Turkish family's pedigree went back even further: on one side Osman was descended from Namik Kemal, the first Turkish patriot and national poet of Turkey in the 1870s, the pre-eminent figure among the Young Ottomans. Still further back Osman was also a hereditary tribal chief of the Menemencioğlu Clan of Western Turkey, and possessed their hereditary insignia.

Yet there was another contradiction. Despite his Turkish name and background, Osman was, as he would often explain, about three quarters Istanbul Greek by heredity, for he had ethnic Greek blood on both sides of his family. And this led him to a passionate commitment to certain cultural causes, the chief of which was the right of the Istanbul Greek Orthodox Patriarchate to re-establish its seminary on Heybeliada. But he was equally passionate about ensuring that Turkey was given a fair hearing in the UK and received the understanding which was its due.

But to those who knew him he was absolutely an Englishman of the very finest sort, a former chairman of London's Savile Club and an Anglican by religion. He could remember being educated in Ankara in his early years at the Ayşe Abla İlk Okulu, but he was also a graduate of Magdalen College Oxford, perhaps the most refined of Oxford colleges, and the ethos of Magdalen somehow never deserted him. The combination of shrewdness, courtesy, and gentle humour that he inherited from his father made him a very singular person. Yet he was not someone who stood aside from events. Over the years he wrote a stream of letters, pithy, short, and witty, to newspaper editors, as well as reviews and articles for the Daily Mail. Writing letters to newspapers is an unequal challenge: the ratio of those published is always low. But the humour, brevity, and good sense of Osman's letters meant that he enjoyed a high 'hit rate'. As a result his name was frequently in the public eye as far as newspaper readers were concerned.

He leaves behind Kabby, his wife, Olivia, his daughter, and his grandchildren, Enzo and Savuka. But he will be sorely missed too in a very wide circle in London and Turkey.