Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionMaureen Freely goes ‘Bosphorising’ with her father, John Freely, in search of her treasured childhood in Istanbul. Could it be that it was all so simple then?

Our first house in Istanbul had a sweeping view of the Bosphorus. So did our second, and our third. But from the room where my father and I are now sitting, just half a hill away, we can see only trees. From time to time we can hear a ship sounding its horn, though. There is also the low roar of traffic passing from Europe to Asia across the Fatih Mehmet Bridge, until the sky darkens and this, too, fades away as the muezzins of Rumelihisarı, or rather their recorded voices, sing the call to prayer.

There seem to be more of them these days. Or is this just my imagination? I ask my father, who informs me that there were three mosques along this stretch of the Bosphorus when I was a child, and there have been no additions, unless I wish to count those in the vast new neighbourhoods in the hills above us. He goes on to do so for me, but I can hardly hear him, because now the dogs are howling. The ezan always takes them by surprise. Like all the towns along the Bosphorus, Rumelihisarı has a long history of street dogs. They roam in packs, protecting us from outsiders with ill intent. But I don’t remember a chorus quite this loud or large.

My father tells me I’m right about that, at least: just above the university campus where he and my mother have lived for more than 50 years, there is now a municipal dog pound. He begins to tell me about the night a large pack of these poor creatures found a way over the wall, but again his voice is drowned out, this time by a low-flying 747. This is not a daily phenomenon – it depends on the wind – but today we are back under the main flight path into Atatürk Airport. From air, land and sea, the new century encroaches.

But there is one thing it cannot seem to change, I say, and that is the light, which is not like any other I have seen. Again, my father agrees. He points to my mother’s watercolours, which adorn every wall. “She caught the light, didn’t she?” he says. In every season, and at every time of day, you have only to look outside the window to know that the Bosphorus is just a five-minute walk away.

My father, at 88, is not as fast on his feet as he once was. So this afternoon we are letting our imaginations take that walk for us. We begin by skirting the walls of the university, passing Tower House, where we lived when I was a teenager, to arrive at the southernmost walls of Rumelihisarı. We picture ourselves standing there, looking up at its stern stones and crenellations, and peering around its base, in search of the armchair boulder in which we’d put so much faith as children. Having settled ourselves into it, we’d turn to our left, to look up the Bosphorus in the direction the Black Sea, and then turn to our right, to look down the Bosphorus in the direction of the city. After we’d done that three times, we’d shut our eyes, recalling every detail, great and small, and make a wish.

I tell my father how comforting it was to survey the Bosphorus from a stone seat so high and securely anchored that not even the most monstrous passing warship could make it tremble. From here, the Bosphorus was serene in its silence. No matter what happened, it would continue to flow. No matter what, I say. My father pauses for a moment, before telling me about the time he stood on the crest of this same hill, to see hundreds of takas sailing into the city. This was in 1976, just before he and my mother tried to leave Istanbul the first time. The taka owners were staging a protest about a sudden rise in insurance rates. They claimed it would put them all out of business, and before long, it mostly did. What a shame that was, my father says. Did I realise there were accounts of fishing vessels of this design going back to 1800bc? “Only to be eliminated in one day with a single stroke of the pen.”

In sadness we gaze down the cobblestone road that runs between the Aşıyan cemetery’s turbaned tombstones and the summer house that was built by an Ottoman poetess just before the First World War and became our own achingly romantic (but also unheated and rat-infested) home in the mid-1960s. Its upper balcony offered a view of the Bosphorus that was framed by the two palm trees rising from a pond that – like the pomegranate and persimmon trees, the gazebos, hedges and flowerbeds, and everything else in its once-magnificent garden – had been left untended for 30 years. After we moved out, the house was rented and then expropriated by the police, to be used as an observation post. Today it sits behind high walls, guarded by an unfriendly pack of Alsatians. But Tevfik Fikret’s house, the Aşiyan Museum, just next door, has recently been refurbished and is, my father assures me, more beautiful than ever.

He asks me if I remember the night in 1964 when one of its watchmen killed another watchman, during an argument about a foreigner’s suitcase. I tell him I most certainly do: I was the one who discovered the blood stains on the snow. “No, you weren’t,” says my father. “It was your sister.” She was also the one to discover the upmarket brothel that was our only other neighbour. The women were very kind to her and her best friend, leaning out of the windows to pinch their cheeks and offer them oranges.

He recalls that other time when one of the brothel’s suppliers tried to deliver half a truckload of oranges to our house in error – along with the beer that took up the rest of the truck. So then I remind my father of the afternoon when a five-star general strode into the kitchen to find my mother drinking a cup of tea alone. “Where are the girls?” he asked. She explained that we were in school. “All right then,” said the general to my mother. “I’ll have you instead.”

It is, my father says, a much more treacherous road, these days – no room for cars to pass, and no room whatsoever for pedestrians who want to live, so we turn left instead to pick our way across the cobblestones of Kaleağası Sokağı, skirting the castle walls to round the bend at the old marble fountain. There’s a lot of traffic here, too: four-wheel drives and Audis and Mercedes parking badly, or pouring in and out of the university alumni club, or collecting children from the new private nursery school that is located on the ground floor of one of the many expensively restored wooden houses that I remember as decrepit and unpainted, draped with laundry, surrounded by dogs and boys, and milkmen, rag and bone men, and their emaciated donkeys.

Did I know that from the time of the Conquest until its 500th anniversary in 1953, there was a village inside the walls of the castle? The inhabitants were direct descendants of the people who had built it. Such a shame to have dispersed them, my father sighs. Then he says, “Perhaps it was necessary. Let’s not get bogged down.”

We climb out of the little valley into Hisar Meydanı, passing the great plane tree, and the gates to my old primary school, and the higher, more forbidding gates to the Pasha’s Library, where James Baldwin lived during the late 1960s. I shall never know that pleasure, which is why I am forever writing novels with characters that do. As we imagine our descent to the shore, I glance up at the glass porch that runs around three sides of the library and seems to sail above the outcropping on which it is balanced.

By now the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge seems close enough to touch, but as we reach the shore, time rolls backwards, until it fades from view. It is 1960 again, and the iskele is no longer a swanky restaurant but a working ferry station. There’s one just coming in now: the man on the deck throws two old and tar-soaked ropes, which the man on the landing loops around poles. The other rolls out two salt-stained ramps, which most passengers sidestep, preferring to jump across despite the signs warning them that it is dangerous and illegal. We do the same, and within seconds, we are off, watching from the railings as the hills of Europe recede and its sinuous shore unfurls. Soon we can see as far as the Point of the Wild Currents in one direction, the tulip gardens of Emirgan in the other.

The sea breeze picks up as we make our way past the takas, the sandals, the sailing boats, and the occasional Soviet tanker. And for a moment I think that we are off to the city again, on one of our Saturday morning explorations – that soon we shall be slipping past the coal yards that have still to give way to paparazzi nightclubs, cypress gardens that have not yet vanished under concrete, and burnt-out palaces destined to become the sorts of luxury hotels that host summits.

My father seems to know where my thoughts are going. “Let’s wait till we’re in the right mood,” he says. “Today let’s stay closer to home.” So we turn back to watch the European shore receding, as the hills beyond it rise. And there, between the towers of Rumelihisarı, is the wooded valley we once called the Bowl. There, at the very top, is the tekke of Nafi Baba, and even at this distance I can still see the candle stubs lining its window sills, and little shreds of cloth fluttering beside them.

We turn towards the Asian shore, which is fast approaching. What season is it? Spring, of course. Late May, early June. Late enough for the Judas trees to have turned those hills pink with their blossoms. Where next? I suggest Kanlıca, and the café under the plane tree where they serve tubs of yoghurt piled high with powdered sugar, but my father opts to keep us on the ferry as it hugs the shore, passing the yalıs that have, with the rolling back of time, lost the harsh polish of money. Once again they are dilapidated relics, their uneven terraces furnished with chairs that don’t match and plants in rusting tins advertising margarine and sunflower oil. We sail past the gorgeous, ancient and collapsing Amcazade Hüseyin Pasha Yalı, and Anadoluhisarı, the little castle built by Mehmed the Conqueror’s grandfather, and the two streams that are known as the Sweet Waters of Asia, but that I remember as sending great ribbons of mud into the Bosphorus after every storm. Between them is the wedding-cake palace in which I never once saw a lit window.

Just beyond is the magnificent Kıbrıslı Yalı. And there is Emin Bey at the landing. In the garden to his right, a manservant is tending to a dozen assorted guests. Once he and my mother were sitting there drinking cocktails of unknown provenance when a young man swooped in on water skis. After allowing himself to be introduced as the future Maharajah of Mysore, he swooped off again, probably because he knew of a better party along the shore. All the best parties on this side of the Bosphorus were at Count Ostrorog’s.

In the days before bridges, the towns of what we called the “other side” were both part of the city and apart from it. The road following the shore only rarely offered views of it. There were many more ferries working the Bosphorus in those days, so it was easy to take one over to spend an afternoon or an evening in one of the little restaurants next to the ferry stations, or under the plane trees just behind them. And if you missed the boat, and didn’t want to wait for the next one, there was always a fisherman who could take you back in his motor.

Sometimes they’d ferry us across to Arnavutköy, which had a bay then, and not a four-lane highway pressed up against the old Ottoman houses with landings they can no longer use. Sometimes they would take us around the Point of the Wild Currents and into Bebek Bay. Do I remember how many fishermen Bebek had in those days? Do I remember the houseboat once rented by the son of the US Ambassador to Egypt? The day after one particularly wild party, my father and a friend went back out in a rented sandal to help him clean up. As far as the eye could see, there were empty champagne bottles, floating belly up.

Güzel Marmara – that’s what Turkish champagne was called back then. I remember it as şampanya. It cost five liras a bottle, and you got two liras back for every bottle you returned. On the day of the Great Bebek Bay Clean-up, my father and his friend rowed back to shore with enough bottles to buy a whole new case. Or was it two? That might have been the day they pooled enough money to buy three or even four cases of Güzel Marmara, and rent a taka to take us all out to Riva, just outside the mouth of the Bosphorus. But equally, they could have just taken us all out for an endless Sunday at Yeni Güneş, the rickety restaurant perched over Bebek Bay. Yes, they were endless, the Sundays on that porch. I remember long tables of men, picking at their mezes and their fish, pouring each other rakı, sometimes holding hands and sometimes not as they conversed in Greek or Turkish or French or Ladino or Armenian but more commonly a mixture of all five, telling each other low, slow stories that would end with a slap on the table, and a long, fierce stare, to be followed by roars of laughter, kisses on foreheads and slaps on the back.

The languages of the Bosphorus mixed openly in those days. Along our little stretch, there were as many working churches – Catholic, Armenian and Greek – as there were working synagogues and mosques. Each community married and buried and even educated its own, but at home and at work, at butchers and fishmongers, greengrocers and bakeries, and in every public space, they wove their lives together. So when the Cyprus crisis of 1964 led to the abrupt expulsion of tens of thousands of Istanbul’s Greeks, we who were left behind felt as if we’d had our own limbs ripped away from us. From that day on, the only Greek we heard was in the handful of restaurants where they still played kantades and rembetika behind closed and guarded doors. But before long, this music died, too.

From time to time, if we were walking around Psychiko in Athens, or Turkolimani in Piraeus, we would find them reincarnated. But even their owners agreed that something had been lost. What wouldn’t they give, they all said, to return to their beloved Bosphorus. Now what would they think, if they could see how many cars and nightclubs and wedding halls and cafés and restaurants and tea gardens now lined its shores, and how few trees?

Sometimes I wonder what it’s done to us, to have known the Bosphorus before the city swallowed it up. Sometimes it seems as if I spend my life clinging to whatever remnant I can find. Sometimes, when I return after a long absence, the only things I notice, and with burning fury, are the things that deface the memories I carry with me, everywhere I go. I do not share these thoughts with my father, who needs to conserve his energy if he is to keep the past alive in stories.

Time to head home now. We fight our way through the crowds and exhaust fumes of Bebek, pausing where the road returns to the shore. Behind us is the apartment block that replaced Nazmi’s, the café where, in the Sixties, my father went to sit every evening, after buying his paper, where he’d made his first friends and met all of Istanbul’s great characters. Shaded by plane trees, its garden was as large as a football field. “Do you remember how the fishermen stored their nets and poles in the back?” my father asks. What I remember better is sitting next to the low wall, listening to the rise and fall of voices I cannot yet understand, and watching the world flow past: stiff-backed ladies with stiff grey hair, arm in arm with men leaning on silver-tipped canes; servants, scurrying past with packages and string bags; wave after wave of students, while behind them, clapped-out buses and 1956 Chevrolets roll past, and the fishermen grill fish, and the chestnut man burns chestnuts next to the man hawking the helva gaufrettes we call paper plates. Beyond them I can see ferries, sandals, takas, tankers, liners, cargo ships and warships, gliding over water that is pink one moment, and silver the next, then turquoise, then midnight blue.

The moon comes up, and everyone claps.

We wave goodbye, and continue northwards along the shore. As we make our way between the joggers and the dog walkers, the pleasure boats and the yachts, Father points up at our first home in Istanbul. I can just about see the large balcony where we held our first parties. And here, before us, are the steps from which my father and his fellow revellers would greet the dawn by stripping off to jump into the Bosphorus. He is telling me about the time they almost swam into the path of a Soviet tanker when my mother’s voice floats in. “Have you noticed,” she says, “how he only talks about the parties? No mention of the hours and days and weeks he spent reading, reading, reading. Everything he could put his hands on! Anything that anyone had ever written about this city! Can you remember how, when he sat down for supper, everything he said dated back to 1120?” I can. Right down to the last detail. For now we are almost home. As we pause at the foot of the Aşiyan, inhaling the turquoise air one last time, my father points to where he once watched a film crew shooting a romantic interlude: a man and a woman sharing a meal at the water’s edge. When the film was in the bag, the actors sped off in a car, and the director sat down with the cameraman and finished off the food and drink.

No sign of them now. We head up the hill in silence. The climb is very steep. The cemetery on our right seems almost endless. As we imagine our way up past the southernmost edge of Rumelihisarı, and the Armchair Boulder, and the Tower House, and over the crest of our hill, and back to the room from which we can see only trees, my father’s stories keep pulling us back.

First he pulls us back to the Tower House, to greet our downstairs neighbour, the legendary Ali. Did I know he was from one of the great Bektashi families – but also a passionate secularist? Did I remember how he’d give up rakı every Ramazan – returning from his law practice early every evening, to stand in the doorway, brandishing a wine bottle at every passing car, while eating pork?

He was back on the rakı when our chimney caught fire. When firemen wearing fluted helmets went rushing in with their buckets, Ali was right behind them, singing ‘Smoke Gets In Your Eyes’. “That was definitely his finest hour,” my father says. Unless it was the time his wife’s boss took the Tower House corner too fast and ran over Ali’s dog. He knocked on the door to give Ali the sad news, whereupon Ali, brandishing a rakı bottle, and clad only in his underwear, marched him to the end of the garden and locked him up inside his chicken coop.

“He was in there for hours, wasn’t he?” I say. My father nods as he pulls away, to list all the friends and illustrious people who are buried in the Aşiyan cemetery. One is Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, whose great last novel I had a hand in translating.

“I almost died there myself,” my father says fondly. This was when we were still living across the road, in Nigâr Hanım’s impossibly romantic köşk. He was awoken in the middle of the night by our Armenian housekeeper, who informed him that her brother and her husband were trying to kill each other in that cemetery. When he broke up the fight, he saw that they were both wearing his clothes.

“And then. Then. Do you remember the dead elephant they tried to deliver to the house a few days later?” It came from the Istanbul zoo, and it was really meant to go to my father’s friend and colleague, Lee, the zoologist. He’d been encouraging the zookeepers to feed it something other than simits. When the elephant died anyway, Lee asked them to send its remains over, so that his students could learn from its bones.

But before my father tells me where this dead elephant ended up, he’ll need to do a little backtracking. Because actually, there were two elephants. No, three. But the second and the third died in customs. It’s just the first elephant that’s buried in the yard above the house where my father and I are sitting, as the trees sway outside, and my mother’s watercolours catch the light.

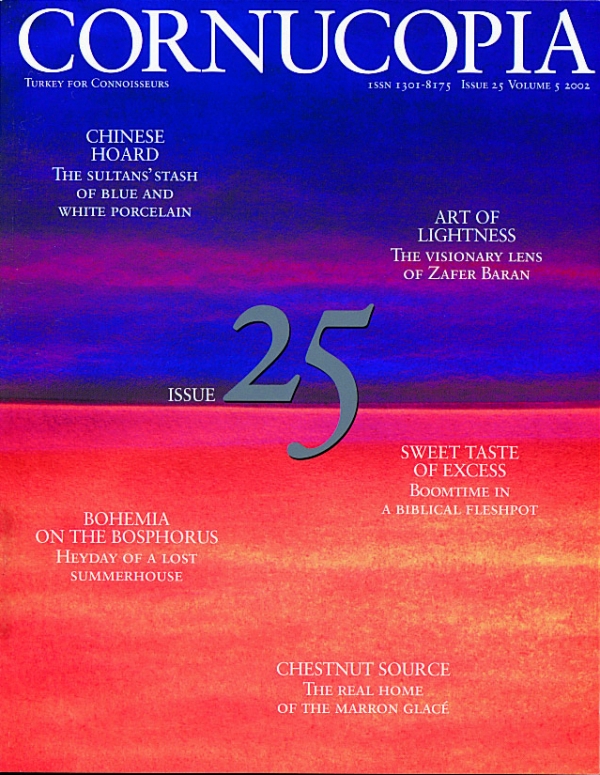

John Freely passed away, aged 91, on April 20, 2017. Maureen Freely’s article was first published in spring 2015 in part 3 of Cornucopia’s Istanbul Unwrapped series, No 52, Bosphorus Requiem. Also see [‘Moving Freely”(http://www.cornucopia.net/magazine/articles/moving-freely/) in Cornucopia 25

The potato was a latecomer to Turkish cookery, but today it is hard to imagine life without it. The humble spud, the ultimate in comfort food, is endlessly versatile,and also comes packed with goodness. Berrin Torolsan serves up some favourite dishes

Üsküdar – its history shaped by three powerful queen mothers and a tireless English nurse – has surprises to offer behind its unprepossessing façade: dazzling mosques, villagey tranquillity and epic views…

Lovely churches, a lively market, enticing ice cream, shady cafés… and they called this the land of the blind. Andrew Finkel introduces Kadıköy, and Harriet Rix mooches around the district of Moda. Photographs by Monica Fritz

Turn your back on the Old City and make for the water. Andrew Finkel takes a drive along the Bosphorus’s lower shore: from the half-abandoned docks of Karaköy, past mammoth cruise ships and hangars for modern art, to the palaces of Beşiktaş and Ortaköy

Andrew Finkel extols the charms of a trip up the western, European, shore of the Bosphorus, whether by water or by road

Over 56 pages, we cross the Bosphorus to explore the lower reaches of the Asian shore. Sailing past the ruins of stately Haydarpaşa Station, we land at the busy Kadıköy docks, wander round Moda’s old cosmopolitan backwaters and head upstream to the sparkling hilltop mosques of Üsküdar

Continuing our tour of Bosphorus villages, we cross back to a more untamed Asian shore. Heading upstream again, we start in Beylerbeyi and Çengelköy, with their grand views of the Old City, and make for the fortress of Anadoluhisari, where the Bosphorus narrows and the yalis are at their most captivating. Our journey ends on the hilltop of Anadolukavağı, with the Black Sea in our sights

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now