Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionTime stands still in the central-Istanbul house where Feyhaman and Güzin Duran, Turkey’s first recognised portrait painter and his artist wife, lived and worked for 40 years. Maureen Freely celebrates their partnership.

In 1910, when Feyhaman Duran was 24years old and teaching at Galatasaray Lycée, he asked a lady of his acquaintance if she might be willing to sit for a portrait. Saying she was too old for such things, she reached into her bag and brought out a picture of a very young girl, suggesting that Feyhaman paint her instead. “I had no idea who the child was,” he recalled many years later. She turned out to be the fourth daughter of the Egyptian prince Abbas Hilmi Pasha. The prince was so pleased with the portrait that – after arranging for Feyhaman to paint his five other daughters as well as several others in his circle – he sent him to Paris to study art.

Following a brief spell at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Feyhaman moved on to the Académie Julian, a private school that had helped in the formation of many leading French artists (among them Bonnard, Matisse, Derain, Léger and Vuillard) and that also welcomed students – women as well as men – from other parts of Europe and the Americas. His days in this international bohemia were numbered. When the First World War broke out, Feyhaman was forced, like so many other Turkish painters then studying in Paris, to cut his studies short. But he took his new ideas home with him. It was Impressionism that had spoken to him most powerfully during his days in Paris, and its ways of seeing would sustain him throughout his life.

He returned to a collapsing empire and a city torn apart by war. Though the despair this must have caused him is nowhere explicit in his work, it was, perhaps, his point of departure. “It is difficult to see beauty,” he later wrote, “but those who can are blessed.” While he earned his keep by painting for the war effort, he kept his spirit alive by also painting for himself. Like other artists of the so-called “1914 generation”, he would gain some notoriety for his nudes, but it was a portrait that won him a national prize in 1916, and to this day he is best known as Turkey’s first and most accomplished portrait painter.

When working with human subjects, it was the tension between the seen and the unseen – the public face and the submerged soul – that most intrigued him. As he would later tell his students: “In portrait painting, there is form and meaning, and neither is sufficient on its own. That is why portrait painting is so difficult.”

He was, by all accounts, a gentle and inspired teacher, less concerned with correction than with opening his students’ eyes. Though he taught his students how to observe the world around them, he urged them to ground their work in the spirit. From 1919 he taught at the newly established Fine Arts Academy for Girls, moving on to the Fine Arts Academy when it opened its doors to painters of both sexes eight years later.

In 1922 he married one of his students, Güzin, who would paint at his side for the rest of his life. They would spend most of those years in the little jewel of a house that Güzin Hanım inherited from her grandfather, a famous calligrapher. It was, perhaps, because they understood their life together as their greatest work of art that they bequeathed the house and all its contents to Istanbul University.

Though the restoration work began soon after Güzin Hanım’s death in 1981, it was not until 2001 that the house opened its doors to the public. But it was well worth the wait. Tucked away in a tiny meydan in Süleymaniye, sandwiched between the Institute of Social Sciences and the Economic Faculty, it soothes the eyes, reminding the visitor that there is more to life than brutalism. A classical column sits at the centre of its small walled garden. At one end is the small but handsome Ottoman house, ingeniously divided into reception rooms and private quarters, with a separate staircase leading to the rooms where a lodger lived on the top floor. At the other is the two-storey Art Deco studio where husband and wife painted together for almost forty years. In both house and studio, old and new sit side by side, complementing each other with an almost capricious grace. In the bedroom, a kilim hangs on one side of a gilt mirror. Hanging on the other side is a nude of Güzin. Next to the Louis XV chair, and underneath the marble-topped dressing table, is a collection of Ottoman ceramic vases. Though the slippers underneath the French bed date from the Fifties, they look as if the wearer left them there only seconds ago. Throughout the house, Feyhaman’s paintings share walls with Persian miniatures, copper trays, Kütahya tiles, Karagöz puppet and works of calligraphy by Güzin’s grandfather. There is hardly a still life without an Ottoman pattern in the background.

While the great thinkers of the day were consumed and sometimes destroyed by the competing claims of tradition and modernity, Feyhaman Duran saw no reason to take sides. His love of modern art did not stop him appreciating Ottoman art. “I love the line as much as I love pictures,” he once said. “The line is itself a picture… In much the same way that a poem can contain a rhyme, a line can contain a poem.”

His generosity of spirit is most evident in his landscapes. When pressed, he confessed to an endless love for nature, accepting all that came from it, and discriminating against nothing. He hated picking flowers: it felt as bad as cutting men’s heads off. “I only paint them,” he said.

Perhaps because he liked to work in the open air, he has left us a legacy of summer views. Some show us the shores of the Princes Islands; others the changing lights and colours of the Bosphorus as seen through the windows of a house in Anadoluhisarı. In almost every one he draws the eye out of shade into light. It is when one looks at many of his paintings in quick succession that one begins to understand what art meant to him.

Though he enjoyed much good fortune in his life – an elite education, a generous patron, a loving wife, generations of devoted students, the respect of his peers, a place at the centre of the artistic establishment, and a house where he could celebrate beauty in his own distinct way – there was also much hardship. He was orphaned at a very young age. As a young man, he again had happiness ripped away from him when, almost overnight, he became an enemy alien in his beloved Paris. Back in Istanbul, he experienced at first hand all the hardships of wartime, and all the humiliations of defeat.

There was no family money to fall back on. Throughout his life he had to earn his keep as an artist, in a country where many viewed art as an unnecessary luxury. But there is no evidence that he ever complained. Not even in his last paintings, when his sight began to fail him, do we see the surge of hope lessening. Instead we see a celebration of colour – which he once described as being as sweet to him as sugar. We see an electric fire burning bright, and a burning house lighting up the Bosphorus at night. In the first we feel the cold of an Ottoman house in winter. In the second we wonder if it is another beautiful old yalı that has gone up in smoke, and if these owners, too, have torched it to make way for an ugly apartment house.

Looking at the portraits, we sense hidden depths. We warm to some of his subjects and pull away from others. Feyhaman was fond of telling his students that artists were only original in so far as they built from their own foundations; what rests at the foundation of his own work is, almost by definition, impossible to put into words. “In certain things, there is no line – only colour. There are no words – only a melody. Art has a great deal to do with that which cannot be said.” Or rather, it is about conveying the full force of the unsaid. It has been three years since I visited the permanent collection of Feyhaman and Güzin Duran at Istanbul University. It was on the same distant day that I paid my only visit to their house. But I am forever returning to its rooms in my mind, most especially when I am in a cold and rainy land, far from Istanbul. Whenever I feel despair encroaching, I revisit his paintings to find my way out.

Feyhaman Duran’s paintings are exhibited on the top floor of the rectorate of Istanbul University (Beyazit). Both paintings and house were bequeathed to the univeristy through the endeavours of the art historian, Nurhan Atasoy.

The rectorate stands on the site of the “old” Ottoman palace, and was originally built as a new war ministry after the abolition of the Janissaries – the gardens made an excellent parade ground. It is worth visiting in its own right.

The Durans’ house stands outside the grounds, opposite the university’s side entrance, hidden by dire examples of 1970s brutalism which obscure the views of the Süleymaniye which the Durans loved to paint. House and gallery are open in office hours, entrance free. Groups by appointment only. Contact the Fine Arts Department (tel/fax +90 212 440 0000, ext 11425). The university’s catalogue of the bequest is unfortunately not currently in circulation.

Robert Ousterhout is agog at the remarkable Georgian churches of the Tao-Klarjeti, the two medieval Georgian principalities between Kars and the Kaçkars

For the English-speaking community of Istanbul the suggestion of aqueduct-hunting in Thrace strikes fear into the hearts of all but the foolhardy. Relentlessly cheerful, Prof James Crow of Edinburgh University would laugh off each misadventure and forge onward.

Leo Gough grew up in the hothouse atmosphere of Cold War Ankara, where his father was director of the British Institute of Archaeology. He recalls tales of derring-do from the larger-than-life visitors and scholars who passed through the institute’s doors

Kate Clow, pioneering waymarker and author of two walking guides to the Taurus Mountains, has now created a guide to trekking in the Kaçkars. Here she describes four breathtaking one-day walks.

By whatever name it is known – whether Karataş Yayla (Black Rock Pasture) or ÇaGrankaya (Singing Rock) – this spur of the Kaçkars is full of drama. Andrew Byfield battled rain and fog to reach its riches

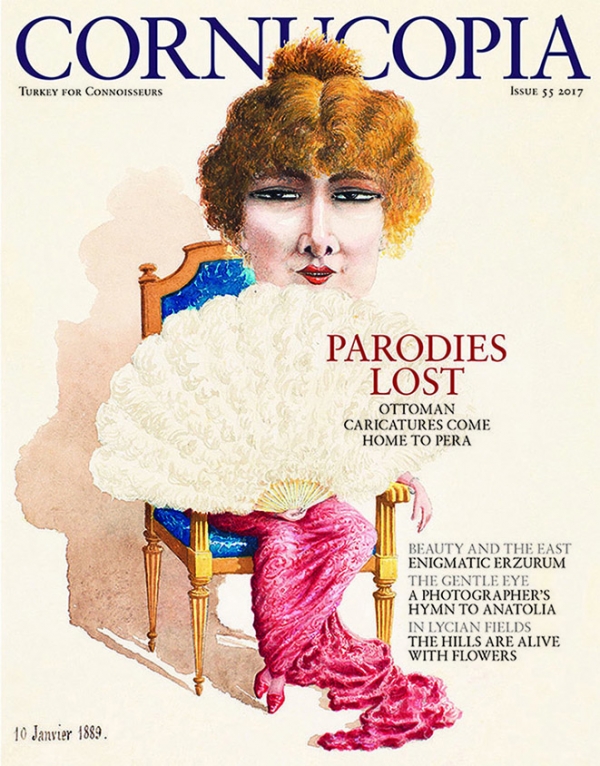

The work of Feyhaman Duran and his contemporaries, once dismissed as unfashionably figurative, is now attracting renewed interest. A recent exhibition at the Sakıp Sabancı Museum in Istanbul celebrated their work. Berrin Torolsan selects some of her favourites

High in the apparently empty Kaçkars, the way of life is as old as the hills. Michael Hornsby joins in the fun at a village festival in remote summer pastures. Photographs by Giulio Rubino

Norman Stone unravels the history of Kars

The Kaçkar Mountains are heaven for butterflies, as the butterfly book author and photographer Ahmet Baytaş, economist by trade, ecologist by nature, discovered when he returned to Yaylalar, the village of his birth

The Turkic Uighurs of Western China have long chafed under Communist Chinese rule. Christian Tyler meets their formidable figurehead, Rebiya Kadeer, who spent five years in prison for protesting against her people’s treatment and now carries on her fight for their freedom from Washington

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now