Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

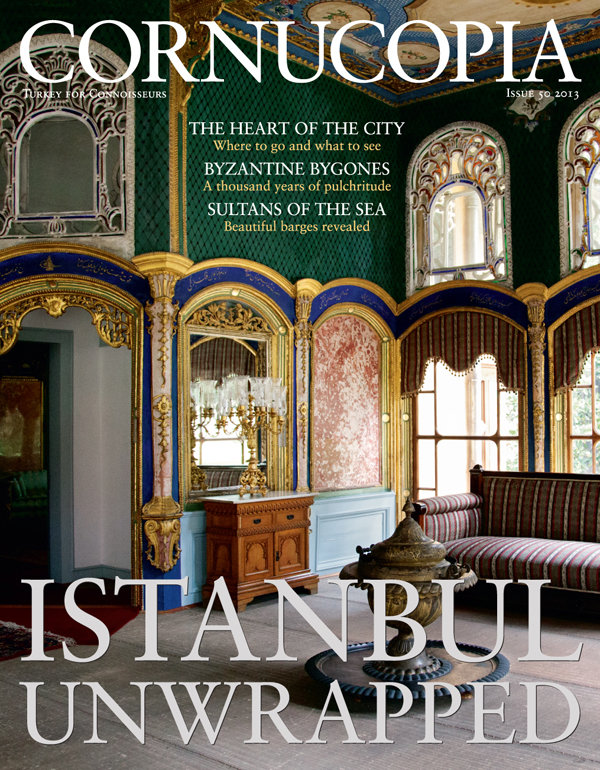

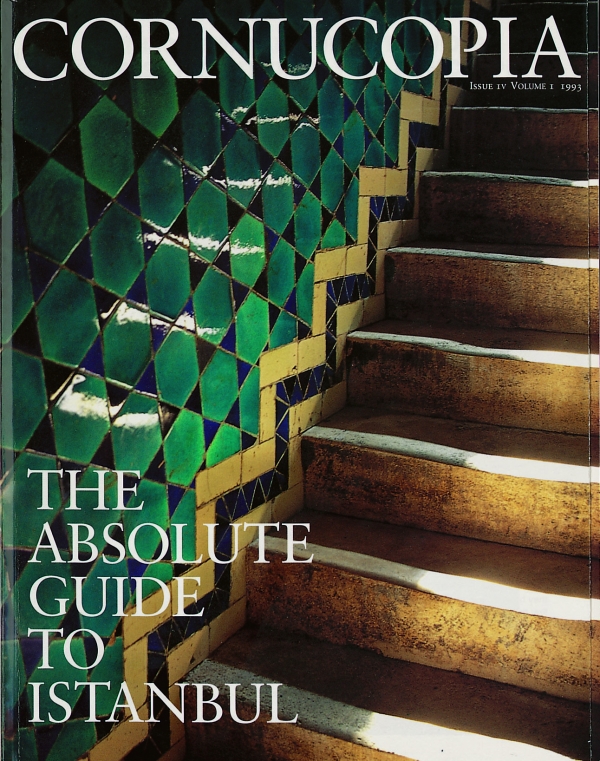

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionPast capital of empires, and heir to an uninterrupted urban tradition that stretches back millennia, Istanbul is all the tourist posters claim. Andrew Finkel traces its history.

Past capital of empires, and heir to an uninterrupted urban tradition that stretches back millennia, Istanbul is all the tourist posters claim. Simply comprehending this legacy, catching sight of its famous monuments, understanding how the drama of the city’s geography has shaped its history, is the instant reward of being here. Less easy to publicise is that modern Istanbul is a city where radical change is the norm, where the population grows at the rate of a decent-sized European town every year, where boundaries are meaningless and where standing still can feel like falling through air.

For a while the city’s proudest metaphor was the suspension bridge finished in 1973 which spans the Bosphorus, connecting Europe to Asia. It proclaimed Istanbul not just as the meeting point of East and West, but as the crossroads of the world. It didn’t take long, however, for the bridge to become synonymous not with movement but with endless slow-moving queues of cars. One bridge spawned another and there are perpetual discussions about building a third. Nowadays, Istanbul is concerned with developing mass transit solutions. It knows that its claim to be a world city is based on its ability to anticipate solutions to future problems.

The trouble, of course, is that Istanbul has always invited conquest. What was true right up to the Allied occupation at the end of the First World War is also true for the inhabitants of the rest of Turkey, who see Istanbul as the promised land. Whereas once the city was its own universe, culturally and physically off to one side of the country, it is now a microcosm of Turkey itself. The post-war city of just one million people began to double in population every fifteen years, to reach 11.28 million at the 2000 census.

From one perspective the history of post-war Turkey is the saga of this relocation of population, and it is mainly in Istanbul that this history was made. It would be wrong to call the integration of these new migrants seamless, but there have been many societies where the transition from rural to urban has been far more painful. Interpol statistics show Istanbul to be extraordinarily safe for a city of its size and, while visitors have to be sensible, it is possible to walk pretty much anywhere, even at night.

All this means that Istanbul has very much recovered from the affront to its dignity in 1923 when Mustafa Kemal stripped it of its rank and declared Ankara as the capital. It was a decision that made strategic sense at the time. The very reasons that gave Istanbul its importance – its command over the exit to the Black Sea and of the crossing from Europe to Asia – made it vulnerable to attack. Yet it is clear that Atatürk also created his own purpose-built capital to escape the imperial cliques of power and decadence. The very act of forcing the British ambassador to leave the well-appointed embassy in Istanbul, a diplomatic mission dating back to Elizabeth I, was a means of wresting practical recognition for the young republic.

It is just one in a stream of Istanbul’s historical ironies that in recent years these roles have more than reversed. Ankara wrestles with the reputation of housing a self-serving bureaucracy and possessing a blinkered view of the rest of the planet. Istanbul, by contrast, is the dynamic face Turkey shows to the world. Even the members of its business community have become the hothead advocates of reform, pressuring Ankara to get on with the reforms that will take Turkey into the European Union and beyond.

If one had to give a date to this change in roles, it would be that brief moment of insecurity at the collapse of the former Soviet Union when Turkey stood shell-shocked and bewildered, like the Japanese soldier still standing sentinel in the jungle after the armistice was declared. Istanbul, with its commercial instincts, was eager to reap a post-Cold War dividend and became the force behind the internationalisation of the Turkish economy that was already gathering pace. The city no longer saw itself at the edge of a flat Earth but at the centre of a new globe. Along with the spur to production, it resumed a role interrupted by two world wars as an entrepôt, this time for the wider region of Eastern Europe, the Black Sea Basin, Central Asia and the Middle East.

Alongside the historic peninsula of sixteenth-century minarets, the city developed alternative skylines of corporate towers, bank headquarters, shopping centres and five-star hotels. There are still alleyways where craftsmen beat silver and copper for the Grand Bazaar. But there are also the giant textile factories of Yeni Bosna out by the airport. Stand in the centre of this new rag-trade district and, within a radius of 500 metres, decisions are taken that are responsible for some $25 billion worth of Turkish exports.

Change also brings loss. Behind every guidebook and memoir describing the city’s marvels is the penumbra of resentment that the aspects of Istanbul that gave most pleasure are under threat or have gone for ever. Istanbul, for all its past, is the enemy of nostalgia.

There was a period in the early 1990s when the pro-Islamic Welfare Party would re-enact Mehmet II’s 1453 siege of the city, using chains to drag their longboats up the hill that shielded the Golden Horn. They dressed up in silly costumes and used tractors, not their bare hands, all to the accompaniment of solemn martial bands. The least convincing part of the spectacle was not the crepe-paper beards but the insecurity it represented. When you have to keep conquering something over and over again, it can never really be yours.

There have been many changes in the intervening decade. The Welfare Party is no more, replaced by a party that eschews the “Islamic” tag and the politics of confrontation. Istanbul is no longer “old-comers” and “new”, us or them, but everyone swimming against the same tide.

There are cities that are great because of the history they contain, and cities that are great because of their extraordinary natural setting. Istanbul, of course, is both of these. But if I had to pin down the greatness of this city, to define the sense of privilege it bestows, the frustration it creates, the pang of exile it inflicts on even the departing weekend visitor, it is that Istanbul is a city that manages to confound its would-be conquerors.

Every spring great shoals swim up through the Bosphorus to breed in the deep, cool waters of the Black Sea, returning south at the end of the summer to the warmer Sea of Marmara and Mediterranean. These twice-yearly visitors to Istanbul are the stars of the gastronomic world and have made the Bosphorus famous for its fish.

More cookery features

Owen Matthews wanders around the Golden Horn’s heady past with John Freely, the man who made strolling through the city an art

This is the starting point for any visitor, the very heart of two great empires. Andrew Finkel explores a world of beauty and grandeur dusting itself down for a third millennium

From the morning of May 31, 1453, until his death twenty-eight years later, Sultan Mehmet II was fixated with re-creating and repopulating his newly acquired capital, Konstantiniyye. Historian Heath Lowry sheds light on the Ottoman Renaissance.

Shopping has superficial connotations, but to set off into this city on a shopping expedition is to explore its culture in the most profound and fruitful way. Elizabeth Meath Baker provides an overview.

Not all Byzantium is buried: in addition to its twenty-odd surviving churches and sundry ruined palaces and fortifications, if you look around any grand imperial mosque, you will inevitably find columns, capitals and other marbles borrowed from its Byzantine predecessor. Robert Ousterhout investigates.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now