Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionNick Thorpe, the BBC’s Central Europe correspondent, should be right in hoping his chronicle (2014–18) of the “age-old phenomenon” of enforced migration will remain a useful reference for many years. The book is made up of first-hand observation and interviews, analysis of national and EU policies, and a four-year account of major developments. The main geographical focus is on the most used of the routes into Europe, starting in far-off Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan, proceeding through Turkey into Greece or Bulgaria and from there into central Europe.

If there is a single epicentre of The Road Before Me Weeps it is Budapest’s East railway station, where the whole crisis came to the boil in September 2015. The inflexible opposition of the Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán to the free movement of asylum-seekers is based on his conviction that this was not primarily a humanitarian crisis but a movement of peoples triggered by economics – the search for “a better life” on the one hand and religious fanaticism (terrorism) on the other.

Ranged alongside Hungary were Poland, Croatia and Serbia, countries that sternly resisted an influx of foreigners, though, ironically, the migrants had their sights set elsewhere. Against these four stood the generally humanitarian point of view of EU officialdom, which held that Europe was obliged by its culture and experience (notably at the end of the Second World War) to hold out a collective hand to refugees fleeing civil wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan – to register them, feed them and resettle them. Chief among these voices was that of German chancellor Angela Merkel, who emerges from this book as a kind of saviour. At her command the German frontier was opened, allowing the river of refugees to burst its banks at Budapest East.

Thorpe was hardly a popular figure with Orban’s government, but it was his number that was dialled by the Hungarian immigration spokesman when the convoy of 100 buses was stopped at the Austrian border. At such moments readers may query the distinction between journalism and activism. Several times, Thorpe is found feeding and otherwise helping his interviewees, once opening his car boot to take out half a dozen watermelons for a group of hungry young Afghans. Episodes such as these are not incidental to the text but the key to its authenticity.

The statistics are all here – the estimated 23 million refugees worldwide in 2018 and, oddly, an identical figure for the pre-war population of Syria, of which a million were killed by the war, five million are refugees in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, six million remain displaced within their own country and another million are in various countries of Europe. Such figures can be found anywhere. The difference here is that we meet these people hiding in maize fields, stuck at train stations and border posts, endlessly waiting for the next step in the asylum process.

Here’s the core of the problem: how to distinguish a genuine refugee driven from his or her home by war or terror from someone moving to another country for the purpose of economic betterment. Thorpe returns to the issue repeatedly, without ever quite resolving it. His own wide experience of asylum-seekers – in Hungary, Serbia, Croatia, Austria, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey – is that people don’t set off on dangerous adventures with small children without a powerful reason – more so than some vague idea of bettering themselves. The risks are known: the media faithfully reports disasters – from the 70 people who suffocated in a meat truck driven by Bulgarians to the overcrowded boats sunk in rough seas in the Aegean and Mediterranean, these last vividly and tragically reflected by the dead body of little Alan Kurdi on the beach near Bodrum, the most notorious photograph of the entire history.

The Kurdi family was perhaps not unrepresentative. They left Kobani on the Turkish-Syrian border as it was being squeezed between ISIS and Kurds in 2013 and crossed to Turkey. Two years later they tried to return, but a renewed ISIS offensive forced them into a further flight. On Turkey’s west coast they paid a Pakistani smuggler for the fatal crossing to Kos. The fee is not mentioned. Elsewhere in the book, Thorpe interviews a refugee-smuggler, a brash young Bulgarian boasting of earning €200,000 in three months.

According to George Soros, as quoted by Thorpe, Europe possesses the expertise and building blocks to manage the refugee problem. Up to half a million a year, Soros claims, could be settled in countries of their choice for an annual sum of €30 billion, much less than was spent yearly from 2014 to 2018 building fences, running camps, compensating Turkey, rescuing leaky boats and so on, not to mention the three or four billion euros a year ending up in the pockets of the people-smugglers – the closest we have to the villains of the piece.

‘How my grandfather took Iznik to Yorkshire’ by Christopher Simon Sykes

Francis Russell drives the highways and byways of Rough Cilicia

Berrin Torolsan on the wonders of white cheese

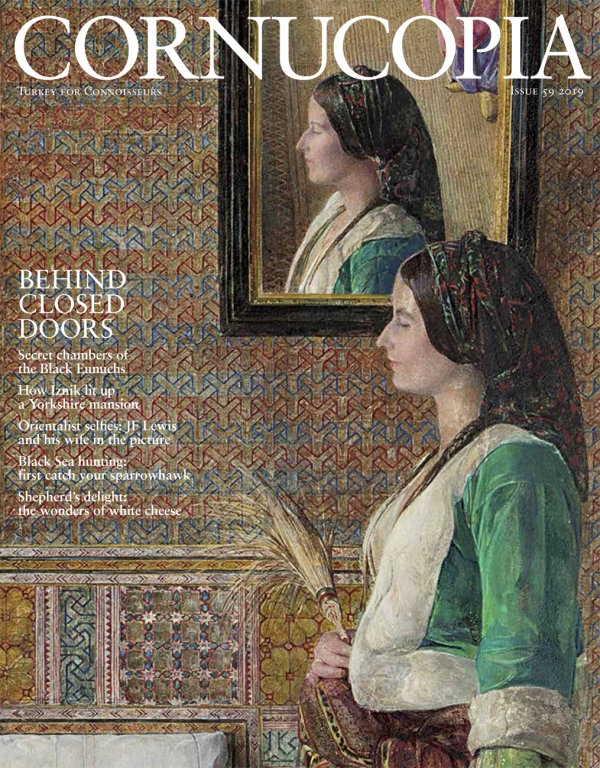

Described by his friend the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray as ‘a languid Lotus-eater’, the Victorian Orientalist JF Lewis travelled to Turkey and Egypt and recreated what he saw of Ottoman life in loving, exotic detail – often painting himself and his wife into his pictures clad in elaborate local dress. Briony Llewellyn looks back over a life of many colours

Fascinated by the many faces of Mihri Rasim, Jamie Leptien asks how and why this unique artist has been ignored for so long

Six millennia before Stonehenge, the dawn of the agrarian revolution came to the now arid Anatolian steppe – and with it came Göbekli Tepe, perhaps the first place of worship built by man. With its T-shaped columns and menacing animal carvings, it is an unacknowledged wonder of the ancient world. But who built it? And what went on here? By Barnaby Rogerson

As the Topkapi prepares to open up parts of the palace long kept hidden, we recall the time Cornucopia was granted rare access to what remains the most secret section of all – the quarters of the Black Agas. These powerful African eunuchs guarded the Harem and controlled the finances of the hugely wealthy Queen Mother. Text by Berrin Torolsan. Photographs by Fritz von der Schulenburg

Yildiz Moran abandoned photography for lexicography at the age of 30. But her decade behind the lens left an astonishing body of work, celebrated this year at Istanbul Modern. By Jamie Leptien

Robert Ousterhout spies the wonders of Anatolia through the eyes of early Western travellers

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now