Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

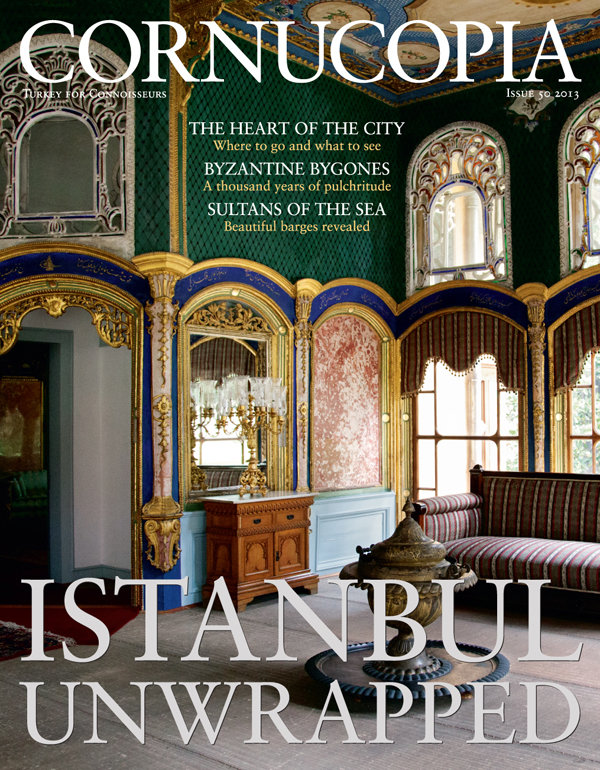

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionÜsküdar – its history shaped by three powerful queen mothers and a tireless English nurse – has surprises to offer behind its unprepossessing façade: dazzling mosques, villagey tranquillity and epic views…

The view from Üsküdar (photograph: Brian McKee)

Seen from the heights of Üsküdar at sunset, the mouth of the Bosphorus is a giant arena. Topkapı Palace, with its many-chimneyed kitchens, occupies the centre ground, dipping down to the Golden Horn on the right, as a tanker sails in from the Sea of Marmara on the left, and a car ferry waits to cross from Üsküdar’s Harem docks to the Old City. Domes and minarets punctuate the skyline: from left, the Blue Mosque, Ayasofya, the Süleymaniye and the Fatih Mosque. Until now the Old City has preserved its silhouette, but modern towers beyond the Land Walls are crowding in.

With this view, Cornucopia 52 begins its tour of Üsküdar…

ÜSKÜDAR PART 1: THE WATERFRONT

SOLEMN PROMISE

The approach to Üsküdar across the Bosphorus is defined by Sinan’s two waterfront mosques, which have framed this gateway to Asia for four centuries. Photographs by Brian McKee

Two very different female icons have immortalised the town of Üsküdar in the Western imagination. Florence Nightingale set up her hospital in Scutari, as Üsküdar was then known, during the Crimean War, using pioneering methods to treat rank-and-file soldiers. And in the 1950s Eartha Kitt gave an unforgettable smoky rendering in quite good Turkish of a popular Turkish song, ‘Kâtibim’, the first line of which is “Üsküdar’a gider iken” or “As I was going to Üsküdar”. Definitely catch it on YouTube before you go yourself.

A landing spot for commuters going to and from Europe, and a working-class neighbourhood, Üsküdar is a busy, traffic-clogged market town where you can buy everything from an Empire chandelier to a plastic button, all overlooked by some of the finest examples of Ottoman religious architecture – mosques that happen to have been commissioned by women. The one thing you might be hard pressed to find is a drink – this is a conservative neighbourhood.

Üsküdar is also now an underground stop for the Marmaray metro, which brings a tube nearly a mile long under the Bosphorus from stations at Yenikapı and Sirkeci on the European side. Indeed anyone trying to get from the Anatolian side to Atatürk Airport in rush hour could do worse than take the metro to Kazlıçeşme, a 15-minute ride away.

The metro saves time, but it will always be more pleasurable to take the scenic route and to arrive on the Asian side by ferry (from Beşiktaş Kabataş, Karaköy or Eminönü). A short hop, it’s a trip one never wearies of. At the iskele, gypsy women sell flowers from colourful stands, while men shine shoes. Buses and dolmuşes run in all directions, south to Kadıköy and north all the way up to Beykoz at the top of the Bosphorus. Rising up behind the buses is Sinan’s İskele Camii (Jetty Mosque, properly known as the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque), and to the right gleam the pale stones of his tiny Şemsi Ahmed Pasha Mosque, where the water laps at the foundations.

When you disembark, pause to get your bearings with the mostly English-speaking staff at the excellent information booth on the quay. Be sure to pick up their free cultural map, ideal for navigating Üsküdar and nearby Kuzguncuk. A guide to Istanbul’s türbes (tombs) is also available.

As a start take a wander through the market area behind the İskele Camii. Among the shops selling cheap clothing and second-hand phones, plumbing and kitchen hardware and bridal gowns, you stumble across antique jewellery and chandelier shops, a modest but bustling fish market, and suddenly the quiet courtyard of a historic saint’s tomb.

Don’t expect the easy charm or sidewalk eateries of Kadıköy, or the shoppers’ frenzy of Beşiktaş; this is a place that the author Selçuk Altun, who has lived here for 20 years and writes of its “dignified Ottoman soul”, calls “the real Istanbul”.

Real, perhaps, in that old Scutari was conquered by the Turks a century before the fall of Constantinople and that Sinan crowned its upper slopes with one of his greatest mosques, the Atik Valide, honouring the Venetian-born mother of a sultan. Real in the serried ranks of five- and six-storey blocks on the back streets of a bustling Istanbul municipality, too often charmless and treeless, but nestling against some of the city’s oldest cemeteries, with tombs dating back to the 14th century. Real in its conservative, workaday feel, and real in the construction that chewed up Üsküdar’s main square to bring the metro under the water.

Rich pickings…

It was with a rich, vinegary tripe soup, followed by a large and strongly flavoured dish of stuffed lamb’s caul (writes Tim Cornwell), that as an outsider to Istanbul I began to understand Üsküdar a little. The packed Kanaat Lokantası (Selman-ı Pak Cad 25), which opened in the heart of the market area in 1933, has the shiny black and metal decor of a period diner; it reminded me a little of Musso and Frank’s famous restaurant in old Hollywood, opened six years earlier, where Raymond Chandler used to prop up the bar. The food at Kanaat is considerably better, though alcohol is not served. Offerings at the crowded tables are oily and delicious and distinctly old-fashioned, and the heavy-duty dessert bar includes a glutinous caramel ice cream.

Down the road, on the ground floor of the İskele Mosque’s elementary school (now a library), is Bingöl Bal Pazarı (Selman Ağa Çeşme Sok 1, +90 532 502 2104), Metin Baydur’s honey shop, where natural-wax honey from the high pastures of Bingöl in eastern Anatolia is expensive but worth every kuruş. Ask for karakovan (natural comb) honey. At Payedar Kahve in Kurşunlu Medrese Sokağı, the side street next to it, an upstairs table affords a close-up view of Sinan’s mosque. Its domes and semi-domes are at their most dramatic here at the back. The steep steps behind the café lead to Üsküdar’s more characterful streets, worth a short meander.

Back around the market, for quick eats there’s a branch of the ice-cream shop Mado (Selman-ı Pak Cad 1), just along from Kanaat. Round the corner I found the tasty and cheap Mavi Konak Kebab Salonu (Hakimiyet-i Milliye Cad 51), with tables upstairs overlooking the harbour; kuzu kokoreç (lamb’s intestines) is one good choice. Mado’s neighbour, Genç Kebap, is another popular spot. But Kuzguncuk, the picturesque community on the Bosphorus just north of Üsküdar, is easily your best stop for light, casual food (see p116).

Üsküdar grows on you, but be warned that getting stuck in its upper back streets, particularly on a summer’s day, can quickly turn into a slog. The wooden houses still cherished in Kuzguncuk are mostly a memory here; you may happen upon one or two – usually in a ramshackle state.

An ideal day’s outing might involve picking out two or three mosques to visit in Üsküdar – with perhaps a bath in the Çinili Hamam – then making your way over to Kuzguncuk for rest and relaxation. With more time, you could also take in Üsküdar’s tombs, a walk south along the shore past Leander’s Tower to the docks of Harem, or a foray in the sprawling Karacaahmet Cemetery on the hills above.

Üsküdar’s little beauties…

Step across the bus-clogged square past Ahmed III’s fountain and you find a more specialised market district, with one street devoted to building materials, another to fishing tackle. In front of it stands the Yeni Valide Camii (New Queen Mother’s Mosque), a handsome 1710 building with a wooden façade. Its darkened stones gave it a feeling of dignified neglect, now being banished by over-vigorous restoration. It was built by Ahmed III’s mother, who lies in a beautiful birdcage tomb open to the elements under an ironwork dome.

In front of the mosque is the start of Doğancılar Caddesi, a long, narrow street parallel to the shore that leads to the Baroque hilltop Ayazma Mosque and on towards Florence Nightingale’s Selimiye Barracks. Close to the Yeni Valide, on Doğancılar, is the inconspicuous but delightful Sahibü’l Çay Âsaf Osman Efendi tearoom (İmam Nâsır Sok 2).

At this rarefied literary rendezvous with four tables, you wait (patiently) for your tray of tea with men who can unlock the mysteries of makams, the modes that make Ottoman music the most inspired in the Islamic world. Tea was Âsaf’s passion, even as a psychology student; he attends the tea harvest on the Black Sea and buys teas from all over the world, which he blends with a variety of spices. An egg timer comes with your pot of tea so that you know when to start pouring.

A few doors along Doğancılar are all the fishing-tackle shops, where they make “flies” with colourful feathers to catch palamut or lüfer (bonito or bluefish) – and lament today’s misguided fishery policies.

Within minutes of the teashop are several landmarks. Down on the shore, the Şemsi Ahmed Pasha Mosque, Sinan’s “little jewel”, has waterfront tombs and the feel of a fishermen’s mosque. The library is under renovation, but the mosque is a delight, with the tomb of its founder, the vizier Şemsi Ahmed Pasha, off to one side through a grille. Perhaps the most perfect piece of classical architecture in the Ottoman world is marred, however, by the dome of the ugly new wedding hall next to it.

For the Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, walk a short way up the hill. The mosque itself remains dilapidated but charming. Built soon after the conquest by a former Byzantine general, it has inescapably Byzantine brickwork, but the grandiose portico and absent courtyard of a Bursa mosque. At the back, in an atmospheric graveyard with an ancient olive tree, is the türbe. Inside, the pasha’s somewhat ghostly turban sits on top of the grave.

There are few remaining wooden mansions in Üsküdar, but in Tephirhane Sokağı, off Doğancılar Caddesi – in the warren of interesting streets surrounding the Rum Mehmed Pasha – is one of the most beautiful in Istanbul. It has no name and the identity of the original owner is lost. The intricate inset balconies confirm the accuracy of JF Lewis’s 1838 Orientalist painting of an Üsküdar café. No one has laid a finger on it. Pray no one will.

Further up Doğancılar, turn towards the sea into Öğdül Sokağı for Angel (pronounced Angle), a restaurant that pioneered exotic fish hors d’oeuvres, many of them visual puns on other dishes – such as tiny simits (sesame-covered bread rings) made not with dough but with sea bass. Angel was named not after a guardian angel but after its founder, though it has been through more than one change of ownership.

If you have caught your own fish or shopped in the tempting fish market, modest Rastgele Mutfak (Doğancılar Cad 106) will cook it for you.

ÜSKÜDAR PART 2: HAREM

HIDDEN HISTORY

Whether you arrive at the busy docks in Harem on foot or by boat, it’s a short step to get off the beaten track. Here you will find Florence Nightingale’s Scutari, coveted city views and ‘the most beautiful house in Asia’…

Most visitors go to Harem to see Florence Nightingale’s theatre of operations during the Crimean War. Her famous Scutari Hospital occupied the Selimiye Barracks (Selimiye Kışlası), which still dominate the hillside, and the modest Florence Nightingale Museum is housed in one of the towers. This gives visitors a chance to see inside a fine 1828 military building round a huge parade ground. But this is First Army HQ and you need permission to visit: the protocol office must be faxed a copy of your passport at least three days ahead on +90 216 310 7929 with the time of your visit (9–5, info +90 216 556 8000, ext 3023).

Harem today is not a pretty place. It is the commercial side of Üsküdar and a transport hub, with docks, car ferries, inter-city buses, and a highway to Ankara and beyond. It wasn’t always so. The confusing name Harem survives from the imperial palace of Kavak Sarayı, built on the cliffs here in 1551, which was a ruin when Selim III used the stone for the original barracks in 1805.

If Harem itself is no great shakes, getting there can be fun. You can walk from Üsküdar along the shore – one of the longest promenades on the Bosphorus – or arrive by car ferry from the European side, much more pleasurable than it sounds.

The panoramic seaside walk from Üsküdar takes less than half an hour (minibuses or buses 12h and 16u are an option). All the way you will have views of the Old City, with Leander’s Tower, featured in the Bond film The World Is Not Enough, in the foreground. Once a lighthouse, the tower (Kız Kulesi, or Maiden’s Tower, in Turkish) is now a restaurant and café. Small boats ferry visitors over.

When you reach a small fishing harbour, be sure to look up: on top of the cliff, glowing oxblood-red, is the last of the wooden houses built to enjoy the Ottoman Empire’s most desirable sunset. With its shutters closed, in the clasp of an old wisteria, the Nuri Birgi Yalı is like a jewel box. The painter Derek Hill called it “the most beautiful house in Asia”. You can still climb the stone path that led up to it from the sea. The old Salacak iskele that stood on the shore now survives only in Sidney Lumet’s 1974 film Murder on the Orient Express.

The Nuri Birgi Yalı is not open to the public, but you can savour the view by looking for a clifftop lane that is not in any guidebook. Keeping the water on your right, weave your way along the cliff towards Harem through well-to-do Salacak to İhsaniye İskele Sokağı. The reward is a place to watch the setting sun reflected in the distant waters of the Golden Horn.

The first house in the street is a perfectly formed but dilapidated wooden house, everything at an angle. The window frames are pencil-thin; a stovepipe fills the air with the scent of burning bay from the tree in its tiny garden. At the other end, precarious steps lead down to an American-style diner on the shore. Otherwise keep the high ground and carry on to Harem along Bestekâr Selahattin Pınar Sokağı.

The car ferry is a surprisingly grand way to get to Harem. It sails across the Bosphorus every half-hour from Sirkeci in the Old City. Climb to the upper deck for a dramatic view of the Topkapı and Galata Tower and, as you arrive, of the Selimiye Barracks.

The Sirkeci–Harem feribot is the last of the Bosphorus car ferries. Conceived in the era of horse-drawn carriages, the pioneering design was the brainchild of two Ottoman nautical men. In 1870 they sent off plans to Maudslay, Sons & Field in Greenwich for a paddle steamer that was identical front and back, with ramps at either end and an upper passenger deck. The Suhulet (Ease) and Sahilbend (Shore-link) arrived in 1872 and were still in service in 1958 and 1967 respectively.

Once in Harem there is little to detain you. Make a beeline for the easily spotted Harem Hotel overlooking the docks, not as a destination in itself (though it has been spiffed up of late and some travellers rave about it), but as a handy place to strike out from.

Climb up behind the hotel to another of Selim III’s landmarks. The lovely late-Ottoman Selimiye Mosque was built in 1801–05. Its graceful steps, curved cornices and poetic graveyard make it delicate without being fussy. The library in the imperial lodge, with works in Ottoman, Farsi and Arabic, adds a learned air. On Wednesdays a huge market takes over the quarter behind it. From here you have a choice of two totally contrasting burial grounds. The British Haydarpaşa Cemetery – a piece of Crimean War history that does not require permission to visit – is the resting place of soldiers and Levantine families (see p86). Take a taxi there, as walking involves busy highways. On the way note the vast Haydarpaşa Military School of Medicine, whose Art Nouveau towers are actually minarets.

Alternatively, walk from the Selimiye Mosque up to the vast Karacaahmet Cemetery, to saunter among its ancient cypresses and turbaned gravestones. At the northern entrance, Hüsrev Tayla’s bold Şakirin Mosque, built in 2009, comes as a shock after the delicacy of the Selimiye. The interior is by the award-winning Zeynep Fadıllıoğlu, the first woman to design the inside of a mosque. Marrying space-age elements and Seljuk design, it has a strange otherworldly beauty.

ÜSKÜDAR PART 3: HILLTOP MOSQUES

QUEEN OF HEARTS…

It may be hidden away in unappealing surroundings, but Sinan’s great Atik Valide Mosque, the Old Queen Mother’s Mosque, on a hill in the district of Toptaş, is one of Istanbul’s architectural wonders. The so-called Sultanate of Women – the period in the late-16th and 17th centuries when powerful females excercised control from the harem – has bequeathed us this mosque and several others in Üsküdar, including the nearby Çinili Mosque.

To reach it from the shore, walk uphill along Hakimiyet-i Milliye Caddesi (it takes 15–20 minutes) or take a taxi or the 12a bus. (Do not confuse it with the later Yeni Valide Camii, the New Queen Mother’s Mosque, down by the main square.)

On foot, you pass one of Üsküdar’s most revered shrines, the Tomb of Aziz Mahmud Hüdayi, who died in 1628. He wrote letters of advice to three sultans, gave the first address in the Blue Mosque, under Ahmed I, and bestowed the royal sword of office on another, Murad IV.

The woman who built the Atik Valide was the luxury-loving Cecilia Venier-Baffo, believed to be the illegitimate daughter of the Venetian Nicolò Venier, Lord of Paros. She rose from being a concubine of Selim II (1566–74) to become the powerful queen mother Nurbanu Sultan. She built her mosque on an open hillside in the 1570s and ’80s, and the complex grew as her power and wealth grew, acting as a magnet. Üsküdar grew in size by a third, and the complex became the meeting point for caravans gathering for the journey to Aleppo or crossing to Europe.

The buildings added to support the mosque – a caravanserai, medreses, shops, slaughterhouses and a tannery – still exist, and even though it is hard to get inside them, just wandering through this Ottoman city in miniature makes the mosque a joy to visit.

Marked by a wonderful fluidity in the arrangement of the buildings, the complex has the hallmark of the masterly Sinan’s final years, when he was at work on his masterpiece, the Selimiye in Edirne, for Nurbanu’s husband. It was completed after her death by her son Murad III.

The mosque has a quality of peace and light that draws you in and draws you back. The Sinan authority Gülru Necipoğlu notes the “lace-like”pulpit and the inlaid woodwork, along with the flowers and trees that spread like fountains over the tilework on the sides of the mihrab. The 17th-century traveller Evliya Çelebi called the Atik Valide a “dome of light”, and so it is, with its soft, pale stonework.

ÜSKÜDAR PART 4: GENTEEL ÜSKÜDAR

KUZGUNCUK: AN OASIS OF CALM

The pace of life in Kuzguncuk, an easy stroll from Üsküdar’s quay, is gentler, the atmosphere more old-fashioned and friendly. You have the leisure to stand and stare – and a good time is assured. By Tim Cornwell…

On the Anatolian shore, Istanbul’s residential settlements start closer to the sea and really do have a stronger sense of community. Kuzguncuk, south of the First Bosphorus Bridge, preserves the sense of an old-fashioned neighbourhood, remarkably since it is so near to the business side of the city. Gentrification has been slow to take root, but there is now a whole series of pavement cafés in addition to a famous low-key fish restaurant. Enjoying Kuzguncuk is a matter of slowing down and allowing its ambience to wash over you, from the cobbled streets and wooden houses to the artists’ studios, quirky shops and eateries that have helped to shape its villagey, bohemian character. From Üsküdar, take the 15 or 15b bus, or one of the many dolmuşes plying the coast road with Kuzguncuk firmly on their list of destinations. It will take only about eight minutes; if the traffic is heavy or the mood takes you, walk it (20 minutes). By bus you crest a gentle hill and alight at the only traffic lights, at the corner of İcadiye Caddesi, the village high street, which strikes inland. People have time to greet and talk here; even the street dogs seem to take a neighbourly, protective interest. You are a world away from Üsküdar, which miraculously hasn’t swallowed up this oasis. That is thanks entirely to residents who have fought several times over the years to preserve their gardens and woods from redevelopment. There are four churches, two synagogues and two mosques. The large Greek, Armenian and Jewish congregations are mostly a memory now, but their legacy informs a tolerant character and style. Take a photograph of the Kuzguncuk mosque on the coast road, Paşalimanı Caddesi, and it is almost certain to include the neighbouring Armenian Church of Surp Krikor Lusavoriç (Saint Gregory the Illuminator). The chief pleasures here are to wander among the houses of this conservation area, some falling apart, others painstakingly renovated; to window-shop, or to pick out a piece from one intriguing artisan or another, then to stop for a bite, relax and chat. It’s hard to have a bad time here. The main part of Kuzguncuk is centred on a few very walkable blocks up the high street, İcadiye Caddesi, which ends in a little square opening onto the water, with benches under the trees. Here is the celebrated İsmet Baba restaurant, with some of the liveliest fish in the city. Next door is the Çınaraltı Café: eat inside, or on one of the benches under the trees at an intriguing fold-out table. There’s a good typical breakfast plate (kahvaltı tabağı). The eggs with spicy sucuk sausage are also first-class, while a simple cheese tost can be washed down with fresh carrot or pomegranate juice. Dilim, the cake shop established in 1977 on the bus-stop corner, is an excellent first stop for ice creams or fancy cakes to take away. Betty Blue (İcadiye Cad 21) serves a light and delicious breakfast of otlu peynirli yumurta, eggs cooked with fresh herbs and cheese. (The bill arrives in a tattered dvd case of the eponymous 1980s French film, underlining the feel of faded cosmopolitanism.) Asude, just around the corner on Perihan Abla Sokağı, is more traditional. It has beans, nohut (chickpeas), bamya (baby okra) and a very good karnıyarık (stuffed aubergine with mince) that melts in the mouth. Since the 1950s, Kuzguncuk has been heavily settled by people from the Black Sea. The Kastamonu Köy Pazarı at İcadiye Caddesi 34 is full of Black Sea produce, with wild-strawberry jam, zesty honeys and white mulberries among seasonal fruit and vegetables. There are delicate, fresh-flavoured ices at Divan Keyfi (No 38) of lavender or tamarind. Or stop at Lebosi (No 86) for chocolates hand-made on the premises. The Harmony Art Gallery (No 42) carries work by local artists, but better still head to the Pita Café (No 41), hub of Kuzguncuk’s art scene. Pita’s owners, all women, show favourite work. One regular is Kağan Önal – “I am not an artist, I am an autodidact” – who works in his studio round the corner, creating “unfunctional objects”, mostly in wood. Scorpions made of bottle tops scale one wall. Two doors down, the sculptor Bihrat Mavitan welcomes you to his sanat mutfağı, his art kitchen, with his “art mafia” family of three generations, all trained at the Istanbul Fine Arts Academy. Bihrat’s work is not contemporary – “not yet”, he jokes. He has held more than 100 exhibitions, and produced three public-art commissions that he can see on Google Earth. His “art kitchen” is an Aladdin’s cave of work and wit. A horse on the wall looks as if it’s sculpted in iron, but is made of leather: “I make new animals from animal skin,” he says. One singular sculpture portrays a local favourite, a man with Down’s syndrome cared for by the village.

One meaning of Kuzguncuk – along with blackbird, or little raven – is the small window of a prison door, which Bihrat likens to the view back down İcadiye Caddesi, framing the Bosphorus. Nearby, the painter Yusuf Katipoğlu is working on a series of daily sketches of Leander’s Tower off Üsküdar – he has done about 500 to date. His corner studio is well worth a visit.

At the 19th-century Greek Orthodox church of Aya Panteleymon, resembling a music box in white and gilt, silvered images of saints around the walls include St Nicholas, patron saint of seamen. Visit the historic sacred spring during Sunday morning services. The Greek Cemetery is a short, steep walk up the hill from the centre, on Tufan Sokağı. With the gate often open, take a wander in the two-level burial ground: most of the graves date from the late 19th century through to the 1980s.

Kuzguncuk’s Jewish community was once so large that it had the name “Little Jerusalem”, with 400 families, but now numbers just a handful. The Beth Yaakov Synagogue is a few yards up İcadiye Caddesi on the left. Built in 1878, it has marbled floors and paintings of Hebron, Masada and Jerusalem on the ceiling. It hosts Ramazan breakfasts for the community.

The Jewish Cemetery is 15 to 20 minutes’ walk out of the village. On a scalding day, wear a hat and carry drinking water. The 20th-century gravestones are in avenues of gleaming white stone with bold inscriptions in the Spanish of the Sephardi community – a defiant echo of what once was. The oldest stones, scattered across the hillside like archaeological remains, date back to the Inquisition (when Jews took refuge in the Ottoman Empire), with generations of names and families now long forgotten. The only gate to the cemetery is on the north side, on Azizbey Sokağı. (For permission to visit Jewish sites in Istanbul, see turkyahudileri.com.)

For a pleasant ramble back, turn left out of the cemetery, and continue until the dirt road ends; turn right, and on the left you will see steps down the hill, weaving between houses. At a house with bright blue railings, the steps come out onto Asker Sokağı. Turn left, and you will shortly meet İcadiye Caddesi. Time for another ice cream.

Excerpts from Issue 53, part 3 of Cornucopia’s four-part Istanbul Unwrapped series: Bosphorus Requiem, pp90–117

Maureen Freely goes ‘Bosphorising’ with her father, John Freely, in search of her treasured childhood in Istanbul. Could it be that it was all so simple then?

Turn your back on the Old City and make for the water. Andrew Finkel takes a drive along the Bosphorus’s lower shore: from the half-abandoned docks of Karaköy, past mammoth cruise ships and hangars for modern art, to the palaces of Beşiktaş and Ortaköy

Andrew Finkel extols the charms of a trip up the western, European, shore of the Bosphorus, whether by water or by road

Over 56 pages, we cross the Bosphorus to explore the lower reaches of the Asian shore. Sailing past the ruins of stately Haydarpaşa Station, we land at the busy Kadıköy docks, wander round Moda’s old cosmopolitan backwaters and head upstream to the sparkling hilltop mosques of Üsküdar

Continuing our tour of Bosphorus villages, we cross back to a more untamed Asian shore. Heading upstream again, we start in Beylerbeyi and Çengelköy, with their grand views of the Old City, and make for the fortress of Anadoluhisari, where the Bosphorus narrows and the yalis are at their most captivating. Our journey ends on the hilltop of Anadolukavağı, with the Black Sea in our sights

The potato was a latecomer to Turkish cookery, but today it is hard to imagine life without it. The humble spud, the ultimate in comfort food, is endlessly versatile,and also comes packed with goodness. Berrin Torolsan serves up some favourite dishes

Lovely churches, a lively market, enticing ice cream, shady cafés… and they called this the land of the blind. Andrew Finkel introduces Kadıköy, and Harriet Rix mooches around the district of Moda. Photographs by Monica Fritz

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now