Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionBlack musicians, White Russian princesses, Turkish flappers… During the Jazz Age, Beyoğlu was a ferment of modernity and decadence.

Writing in 1922 for the Toronto Star, the young Ernest Hemingway, yet to make his name as one of the 20th century’s most consummate prose stylists and infamous drinkers, mixing his metaphors somewhat, compared nightlife in Europe to “a sort of strange disease” that had always existed but had been “fanned into flame” since the war and burned an entire generation.

The 23-year-old reporter admired the civilised and amusing Paris scene. Berlin was “sordid, desperate and vicious”, while Madrid was merely dull. Nothing, for him, compared for excitement to the nightlife of Constantinople. Hemingway was in his element in the cut and thrust of old “Constan”. He evokes a society of insomniacs, wakeful for most of the day and all through the night. “No one who has any pretentions of conforming to custom dines before nine o’clock at night. The theatres open at ten – the night clubs open at two… the disreputable night clubs at four…”

The Jazz Age was in full swing, and Constantinople was “doing a sort of dance of death”. Jazz, like its sisters from the bustling urban streets of the early 20th century, the tango, flamenco and the Greek rembetika, boiled up and spilled over from Paris to Berlin, from Cairo to Bombay and Shanghai. In the fecund breeding ground of Pera (today’s Beyoğlu), in a city whose imperial purpose was gradually slipping away, the sounds of George Gershwin’s ‘Swanee’ echoed through the nightclubs; dancers adorned themselves with peacock feathers and learnt to Charleston; noble Russian refugees waited on tables; and opium and cocaine fed the fervid imaginations of the city’s chancers and arrivistes. Jazz, which terrified the Establishment across the Western world, titillated the international avant-garde and gave voice to the mood of the “Lost Generation” across Europe.

Turkey, born out of the maelstrom of the Great War and poised to embark on a dramatic period of modernisation, couldn’t quite decide what to make of it. Following its occupation in 1918, the imperial city had been inundated with foreigners. Occupying Italian, French, British and American troops patrolled the streets. Refugees from Odessa – White Russians fleeing the Bolshevik revolution – peopled the restaurants and cafés, or begged and loitered on corners. The bars filled with journalists, chancers and writers, the flotsam of the war cast up on the strand of Pera. Mufty-zade Kemal Ziya Bey, a Turk who had lived in America for a decade, put it succinctly: “Pera shelters all the foreigners in Constantinople, from the high commissioners of different nations and their immediate retinues down to the worst kind of adventurers. And of course there are many more adventurers than high commissioners.”

The arrival of General Wrangel’s fleet from Odessa in 1920 dramatically changed the face of Constantinople. Until its eventual closure in 2011, the tenacity and resilience of the famous restaurant Rejans gave the false sense that the city’s Russian colonisation had happened only recently – not almost a century ago. People who remember Istanbul in the 1960s repeat the familiar lore of ballerinas, concert musicians and Tolstoyan princesses working behind the tills at Rejans. The story of the Western sophisticate, passing through Constantinople, who is moved to tears when he recognises his waitress as a grande dame of St Petersburg society he had known in Paris before the war is a staple of Beyoğlu mythology.

The reality of the Russian exodus was far grimmer than such fairy tales. Of the 150,000 émigrés who made their way through the city, 30,000 were still there in 1922. Half were destitute, fed by relief agencies; the other half found jobs however and wherever possible. Constantinople Today, a book published in 1921, related: “Russian refugees are everywhere, selling flowers, kewpie dolls, oil paintings of Constantinople, cakes and trinkets, books and newspapers printed in Russian. They sleep in the open streets and on the steps of the mosques.

For help in writing this article Thomas Roueché would like to thank Carole Woodall of Colorado University, author of a forthcoming book, ‘The Decadent Modern: Cocaine, Jazz, and the Charleston in 1920s Istanbul’. Thomas Roueché: tom.roueche@gmail.com

Issue 51, Summer 2014

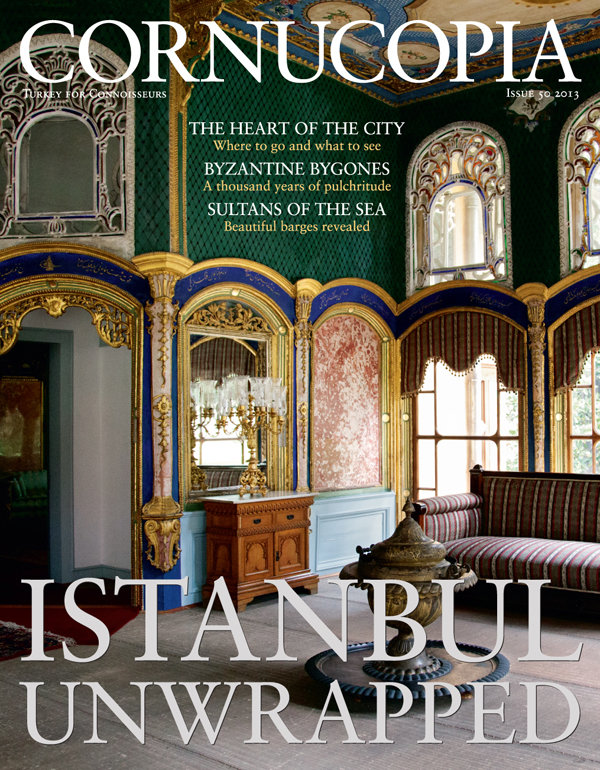

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

John Carswell introduces the mesmerising entries in this year’s Ancient and Modern Prize for original research

With 19th-century Istanbul in thrall to the music of Italy, an extraordinary theatre was born, the creation of one rather ‘odd character’. Emre Aracı tells a tale of comedy and tragedy

For 700 years, the European quarter was home to Genoese, Jews, Greeks and many others. Norman Stone charts the district’s changing fortunes

Maureen Freely recalls the artists and writers who enlivened her childhood with their flamboyant bravado and unspoken sadness

In the very thick of the city, with its fret and fuss, belching traffic and urban sprawl, lies a glade scented with linden blossoms. Here the young Sultan Abdülmecid built a jewel of a palace, grand but tiny, which is still a green oasis and place of escape. By Berrin Torolsan

Until the 20th century, visitors would sail serenely into Istanbul to disembark opposite the Topkapi. After this spectacular start, reality would set in. By David Barchard

For more than two centuries the Ottomans were obsessed by the elegance of the tulip and grew over 3,000 varieties, each characterised by almond-shaped petals drawn out into an exaggerated taper.

With its hundreds of different shapes, pasta is today one of the most widely consumed and enjoyed of all the staples

Across the Golden Horn from the Topkapı and the bazaars is the European City, where fortunes have for centuries been made and lost.

Patricia Daunt extols the palatial embassiess that adorn the heights of old Pera. Photographs by Brian McKee

As the old European quarters flourished in their seclusion, Sultan Abdülmecid had a dream – and expanded to the east

The Sakip Sabanci Museum has just celebrated 600 years of diplomatic relations between Poland and Turkey. Jason Goodwin finds deep-rooted affinities between the two countries

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

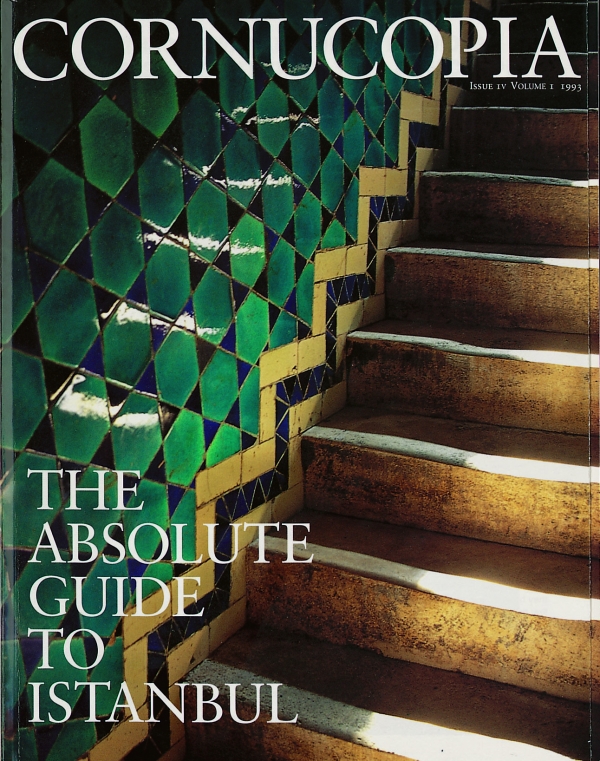

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now