Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionA revealing new show that brings the Topkapı Palace to life

Few places are so shrouded in myth as the Harem of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. Travellers longed for a glimpse of what went on within its well-protected walls, and European artists gave rein to their fantasies in flamboyant paintings.

In recent years the Harem has been refurbished and sections previously hidden from public view have been opened up, but it is bereft of life and of the myriad objects that sustained it. The present exhibition showcases sumptuous and everyday things, both those used by high-status women – princesses and the sultan’s concubines – and those of the slave women who served them.

These include seals, garments and textiles, boxes, jewellery, combs and mirrors, cradles and toys, writing implements, saddles and archery bows, musical instruments, Chinese bowls, vases and flasks, chess sets and shadow puppets.

The exhibition also features portraits of sultans who influenced the architecture of the Harem. Although there has not been a full architectural survey of the precinct, the main phases of its development are understood. Contrary to the conceit of the popular TV soap Muhteşem Yüzyıl (Magnificent Century), the sultan’s women remained in the city-centre palace built by Mehmed the Conqueror, until the 1540s, when Süleyman I merged his private and public household (already at the Topkapı), and building began in earnest.

Fifty years later, Murad III greatly extended the Harem and transformed it into a key state institution headed by the Chief Black Eunuch. A miniature showing the first incumbent, Habeşi (Ethiopian) Mehmed Ağa, before Sultan Murad, comma is displayed alongside documents hinting at the extensive financial responsibilities that made this office so powerful.

The catalogue misleadingly refers to all Harem women as “concubines”, a term properly used for women who had sexual relations with the sultan. One who most certainly did was Hürrem Sultan, whose passion is on display in a letter to her husband, Süleyman. We also see a moving plea from his half-sister, Fatma Sultan, to their father, Selim I, to be released from marriage to a brutish husband. Every time a document from the Ottoman court is published, we can sense the degree to which more generous access to the palace archive will fundamentally change our understanding of the dynasty.

The wealth of previously unseen things brought out from the palace depots humanises the Harem’s long passages and cheerless reception rooms. It is an art historian’s exhibition and focuses on the objects themselves – although they are uninventively displayed – rather than on the history of the Harem as a political force. Informative essays and explanatory notes in the lavish catalogue (in Turkish and English) are written by those who know the place best, the curators of the palace collections. As we roam the empty spaces of the Harem today, we can now better imagine the vibrant life that was lived there and the women for whom it was their whole world.

The best table grapes in Istanbul are the fragrant, delicate skinned çavuş from the northern Aegean island of Bozcaada, ancient Tenedos, and the sweet sultaniye grapes from around Izmir.

Maggie Quigley-Pınar describes a book of photographs that evoke the spirit an almost-forgotten modern era: Istanbul in the 1970s

John Carswell pays tribute to his friend Honor Frost, doyenne of underwater archaeology

James Crow on Istanbul’s amazing system of aqueducts

They were stigmatised and despised, and eventually they were closed down. But what would Turkey be today without the Village Institutes, its bravest educational revolution, and the young people they empowered? Maureen Freely tells the moving story of the institutes, the subject of a new book and exhibition

The lethal mischief of Canon MacColl, by David Barchard

The Istanbul diaries of Gertrude Bell, now available online, reveal her astonishing transformation from socialite to scholar and political observer. By Robert Ousterhout

As Turkey and the Netherlands celebrate 400 years of diplomatic relations, Henk Boom highlights the twenty turbulent years that Frederik Gijsbert, Baron van Dedem spent as ambassador to Constantinople

Simple on the outside, some wooden village mosques had an added portico reminiscent of galleries opening onto the courtyards of private houses in the region. Inside, pillared halls and colourful painting on the wooden structure and on the walls make for a warm, joyful space. Photographs by Tarkan Kutlu

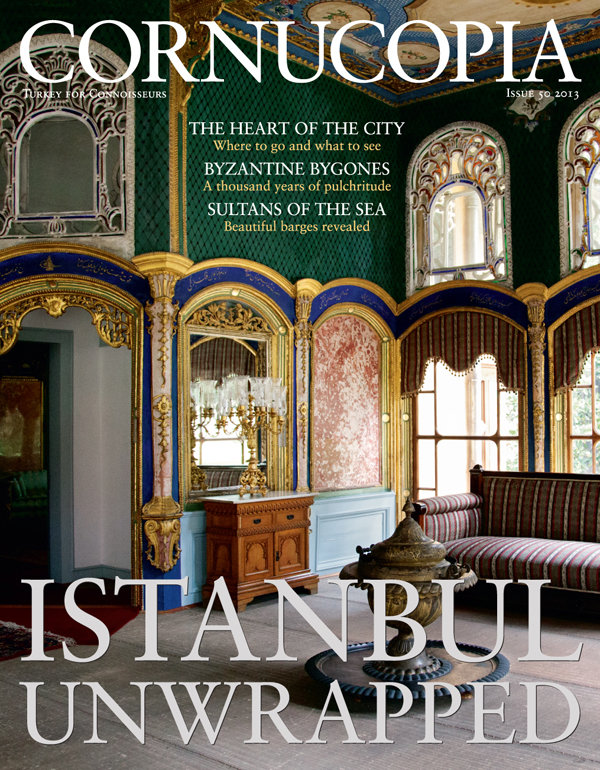

Abdülhamid I and Osman III’s private quarters in the Topkapı. Photographed by Fritz von der Schulenburg

Sagalassos, the remote site in southern Turkey where a giant statue of Emperor Hadrian was discovered five years ago, is the driving passion of Marc Waelkens. The Belgian archaeologist, whose new book is now available from Cornucopia, talks to Thomas Roueché about his pioneering work as director of excavations

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now