Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionCornucopia’s editor and publisher spent nine days in October 2012 exploring the natural wonders and pondering the history of long-suffering Crimea – from the towers of Tatary to the tombs of Scythian kings, from clifftop citadels to an underground castle, from Balaklava to the beaches of the Tsarist Riviera. This is a diary of their travels

Day 1 Simferopol

Two Sashas greet us at Simferopol, the capital of Crimea, where the runway was built for spaceships to land: Dark Sasha, our swarthy interpreter, a mountain of a Ukrainian from Rostov, full of laughter, and Fair Sasha, our driver, lean, blond and full of smiles. In the sleepy city we drop off our bags at the baroque Ukraina Hotel. Opposite is a newly rebuilt cathedral with gilded domes. Behind us is the Salgar river, reduced to a trickle by months of drought. A tram clangs past.

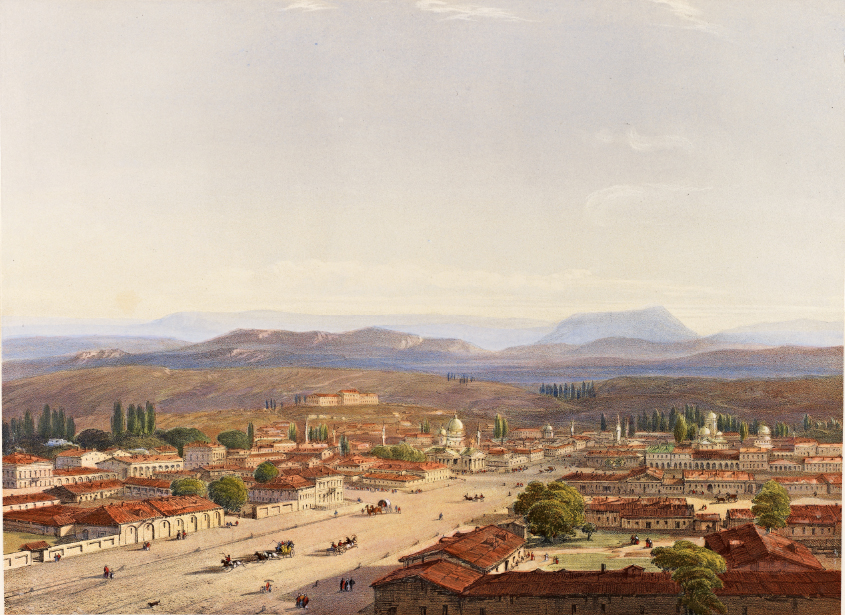

Travellers complain that this is a flat city of wide streets and low houses, just as Potemkin planned it in the 1780s and Carlo Bosoli drew it in the 1840s (above). That’s why we like it.

Our mission is to find out what happened to Crim Tartary, the land of the Crimean Khans. But first we want a taste of the fabled Yalta Riviera. Crimea – part of the new nation of Ukraine since the breakup of the Soviet Union – is small enough that we can drive over the mountains to Gurzuf on the south coast for lunch (below), take a walk along the pebbly beach, clamber up through the Nikita Botanical Gardens, and be back for dinner.

Later we stroll from the parliament of the Crimean republic, the ‘Pentagon’ as it is known locally, via a labyrinthine underground flower market, to old Akmesçit, once the quarter where the Crimean khan’s right-hand man had his palace. At its peak in the 17th century, the palace was surrounded by 2,000 tiled adobe houses. The day ends at a popular Simferopol pizzeria in Pushkin Street.

Day 2 Bahçesaray

Breakfast is raucous because of the piped music, but the porridge is delicious, as are the industrial lozenges of scrambled egg.

We feel sorry to be leaving the glittering baroque comfort of the Ukraina, despite its lack of a lift. We drive through the endless outskirts, past little orchards with low houses flying the blue and yellow flag of the Crimean Tatars, which sports the three-armed symbol of the old Khanate. This time we travel southwest, down a broad river valley, with low, angled escarpments on our left and the flat tabletop Çadır Dağı (Tent Mountain) beyond.

As a modest new town spreads across the undulating plain to our right, we turn left into a narrow ravine to find the capital of the Crim Tatars, old Bahçesaray. This is the Turkish spelling (the name means Garden Palace), but there are myriad other renderings – Bakhchysaray is one. No sooner are we there than we are on the doorstep of the Khan’s Palace (the Han Saray). It takes time to enjoy the courtyards, pavilions and shady benches. Each part of the palace is its own fiefdom, so you need change for lots of inexpensive tickets as you wander round.

The town includes delightful terraced restaurants serving chunky grilled kebabs, mantı (stuffed pasta), and the two Tatar staples, çibörek (a lightly fried pastry with a succulent mince filling), and yantık, the same but griddled. We enjoy all three for lunch with the perfect accompaniment, green tea, for which the Tatars developed a taste when they were exiled to Samarkand by Stalin. After lunch we stroll down to the workshop of a master jeweller specialising in filigree, another charming Tatar who returned not long ago from Central Asia.

Farther up the ravine, where the chalk cliffs are dotted with caves, we reach the quarter of Salacık, where the khans built their first palace. A magnificent but austere mausoleum houses the tombs of two of the early rulers. Under the trees behind it is the grave of the great educator Ismail Bey Gaspıralı. The other places we visit there are the bizarrely named La Richesse historical museum – a treasure trove of maps and prints about Crimea, established by a Tatar lawyer from Lyon – and the Zincirli Medrese, a classic early Ottoman school with deep arcades, now beautifully restored.

Having switched his snazzy bronze Honda for a more functional Lada with the axles of a tank, Fair Sasha speeds uphill over rocky tracks to catch the most sensational sunset view in the whole of the Black Sea, at Chufut Kale, the Jewish Fortress. On the way back through Bahçesaray, we take tea with Bahtıgül, a dynamic young Kazakh woman whose hotel on the hill behind the palace would be the place to stay another time. Then we head in the dark for Sevastopol.

In this port built by Potemkin as a launch pad for the conquest of Istanbul, and the only place in Crimea that feels like a city, our hotel is the sturdy Sevastopol. Dark Sasha takes us down to a quayside fish restaurant, which turns out to be up a tree. A party is in full swing on the lower branches, so we climb up to crow’s-nest level, where we negotiate well-cooked fish in the dark. We are joined by a colleague of Sasha’s and the colleague’s husband, a razor-sharp former submarine officer. We quiz him, of course. Did he get bored during his three months underwater? Not with ten men to take care of. Where did they go? Nowhere. It seems the sub stayed in the caves of Balaklava.

Day 3 Sevastopol

Breakfast is on the splendid colonnaded terrace of the Sevastopol Hotel overlooking Artillery Bay. We take an early-morning stroll along the quay, then set out for the day.

Chersonesus (Kherson), a great city in classical times with a few remaining columns and a mass of shoulder-height ruins, is where the French camped during the siege of Sevastopol. We are happy to find our first local market. We buy pears, apples and delicious buns, and watch watermelons flying onto the shelves from a local farmer’s van.

A motorway whisks us through vineyards to the cave monastery of Inkerman with its pretty rock-cut chapel. It is surreal to look down from the balcony of the chapel to see a bright pink locomotive rumbling through the monastery garden a few feet away.

At Kökköz our purpose is to sample walnut jam, a Tatar delicacy. But before we find it, we stop at a beautiful lake where horses are being herded. Across the water, rising above the forest, are the cliffs of Mangup Kale, the last place the Goths called home. A day would be needed to get there and back.

Outside Kökköz, where the forests close in, Dark Sasha takes us to the hunting lodge built by the mother of Prince Felix Yusupov, notorious for murdering the charismatic “mad monk” Rasputin in 1916. His mother gave this wonderful retreat, with its wide terrace and viewing tower, now semi-derelict, to her Romanov daughter-in-law, a niece of the tsar’s.

After filling the boot with jars of walnut jam, we continue south, up through dense forest, across a mountain pasture grazed by sheep, to the beauty spot of Ay Petri. We see the Yalta Riviera a thousand metres below, swathed in clouds. Under canvas a cheerful Nogay Tatar couple feed us splendidly: huge chunks of skewered lamb from their own flock, with more green tea.

Another morale-booster comes when we reach the coast at the end of the precipitous drive. On a hill above Yalta we find Chekhov’s evocative, lovingly tended White Dacha, with its myriad fruit trees, and box-hedged paths designed for pacing.

Although it is a lovely house and he had many visitors (the piano Rachmaninov played is still there), Chekhov was not happy in Crimea. By contrast, Tsar Nicholas II was delighted with his Livadia Palace, which was rebuilt so as to be flooded with light. Most poignant is the nursery wing, with its mementos of the children – exercise books, photographs and watercolours.

We then race off into the night back to Sevastopol. At dinner in the hotel, we ask about Chicken Kiev. There is some confusion, but the chicken that arrives is better than anything we have in mind. The Inkerman wine goes well with it, too. Day 4 Sevastopol

Today we follow the British and French armies in reverse. They landed in the north near Yevpatoria, left their bags on the boats, not thinking it might rain, and, without tents, were already soused on night one.

But first we take the little iron tub of a passenger ferry across Sevastopol harbour.

The sea is perfectly calm at first, but a good swell meets us halfway across as we pass the gap in the sea walls. It crashes against the quays of the white stucco neoclassical palaces along the shore, flinging spray high into the air. On our left, behind a gargantuan Dnieper river steamer, are monumental statues commemorating the Soviet Hero City.

Our destination is the Mykhailivska Battery on the opposite shore. The path from the jetty leads up the hill past useful shops catering to tired office workers on their way home. The iron gates to the battery seem shut, but swing open with a gentle nudge. The stone walls are still shell-pocked. Inside is an extraordinarily good museum to the Crimean War. Each participating nation has a flag (the Turkish one is apparently at the cleaners), and some have jukebox-like music. This wonderful collection of memorabilia, we learn later, is privately owned, like La Richesse.

Back we go to the hotel, sad not to have longer to explore Sevastopol’s many inlets. Then we whizz off to Balaklava, dipping into a fantastic wine shop; it is early to sample wines, so we carry off five untasted bottles for our wine correspondent in London.

Balaklava, to be honest, is a let-down – as the British Army found. The view is no doubt spectacular from the Genoese Castle, but in the bay it is cramped and grey, and the most exciting thing about it is the grim concrete-rimmed entrance to the subterranean caves that hid Russia’s Cold War submarine fleet.

A gigantic hotel-cum-casino has sprouted on the shore facing the little fish restaurants, blowing to smithereens any chance of the village turning into another Bodrum. We have a quick bite of fish, resisting an offer of baby lüfer, the blue fish of Istanbul, as it turns out that they spawn here. Lüfer take six years to mature and on the Bosphorus it is considered sacrilege to eat them until they are at least 20cm long. In Balaklava they are the size of your thumb.

On we hurtle up the Valley of Death to the Inkerman Valley, covered with vines, pausing at memorials to the fallen. The Turkish one is new and took years to build, the process being stopped time and again by the Russians. We are all rather pleased to find it in the end, hidden in a glade of pine trees. Soon dachas will cover every square metre of this drear plateau. Some dachas are huge, standing in tiny gardens.

Alma is our next stop, halfway up the fertile west coast. It has some fine war memorials, particularly the Russian one.

A sharp left in the middle of nowhere, and we are crossing a spit of land leading to Yevpatoria on the horizon. Kezlev to the Tatars of today, Gözleve to the Ottomans, it has none of Sevastopol’s gravitas. But once we locate our hotel, the Imperia, on tram route no 1 – where, unusually, the Tatar receptionist understands not a word of Turkish (he is a Kazan Tatar) – we walk through the old town. At the grandiose place of worship of the Karaim Jews, the kenesa, we perk ourselves up with sparkling buza in the delightful café. A lot of the surrounding streets have been gentrified in an unfortunate way. At the 16th-century Juma Jami, we are dismayed and angry to be refused entry on the grounds that we aren’t coming to pray. We soon set things straight.

The 15th-century Ottoman gatehouse, whose tower, the Odun Bazaar Kapısı, Tatars recently found the funds to restore, turns out to have an ambitious café on an upper floor, with good-looking young Tatars serving wonderful coffee and pastries. For dinner we take ourselves off to the elegant Anna Akhmatova restaurant, with its between-the-wars Central European feel.

Day 5 Yevpatoria

After a brisk swim off the golden sands and a breezy stroll along the promenade in front of the Imperia, we are ready for anything. The drive to Kerch, with lots of pauses, turns what should be a journey of three-and-a-half hours into eight.

A few miles out of town, we visit the Scythian and Greek remains at Kara-Tobe. Our guide is so eloquent that we assume she is the archaeologist, which greatly amuses her. After skirting Simferopol, about which we already feel nostalgic after our one night there, we set off across the straight road where the 19th-century traveller Karl Koch remarked on the beautiful camels.

At a place improbably called Akropolis, an austere plains village with low mud-brick houses, we meet the ceramicist Rüstem Skibin. He is one of the stars of the Tatars’ artisan revival, and his pretty courtyard garden has borders of woven hazel.

Then comes Karasu Bazar (the Ukrainian Bilohersk), where we see no sign of the great city of old, just a village with a handful of well-preserved low houses. Strangely, the school is a concrete block six storeys high. Cevat Ağa, an old Tatar journalist, opens up the tiny Tatar Ethnographic Museum and tells us tale after tale about life in old Crimea. All the minorities get lumped together as Tatars, he says. Gypsies, Nogays, Tatars, Turks. There’s so much more to it. He wants to take us up onto the white cliffs of Akkaya, where the elders met to choose their khan, and to see the oak tree where the clans gathered before heading off for war. We promise to come back.

Next stop is Nariman’s, a busy café on a wooded bend in the highway, for one of the best meals ever: more fabulous çibörek and yantık, and delicious stews. On then to the great steppe, via the sad old village of Eski Kırım (Stary Krym, or Old Crimea), once the populous capital of the Golden Horde’s Crimean Yurt – a second Baghdad some say.

It is dusk in Kerch and finding a room is no easy matter. Our first choice of hotel has just two good rooms, overlooking the church of St John the Baptist, and they are taken. We try the Meridian and two sanatoria, then the Fishka, a smart restaurant with rooms by the harbour – also full. They recommend the Edelweiss on Mount Mithridates. What a find it is: pristine and with a brilliant view. Before we have time to let the ice melt in our wine, Ivan, the owner, is waiting to show us to our room. The fluorescent lights are daunting, but the bedside lights are fine. All the rooms share a spacious terrace. Russia twinkles on the other side of the Cimmerian Bosphorus. Pasta and more wine at Fishka seal the day.

Day 6 Kerch

A grey day in Kerch, and very low-key. It starts brightly enough. The view over the trees from our perch halfway up the Mithridates Steps is a wonder, and the square at the foot of the steps is filled with the sound of bouncy piped music, which snaps on at 8am. In the Archaeological Museum, a timid curator feeds us closely written laminated pages packed full of fascinating stuff in impeccable English. The original famous museum, looted during the Crimean War, dates back to 1826. It has moved to an old merchant’s house on the promenade and has a fusty untouched charm. One could spend hours there – and that is without even seeing the museum’s heavily guarded Scythian gold, which requires prior notice.

Back in the car, we meander round Kerch’s outskirts. In retrospect each sight is more extraordinary than the last, but one gets blasé on day six of any tour. General Totleben’s “invisible castle” is true to its name. It takes an hour to find it, and when we do, Fair Sasha regrets having handed back the sturdy Lada, so terrible is the road, built of loosely assembled blocks of concrete. Behind a fortress gate, the bullet-headed guide in baseball cap and shades dealing with the tickets is crestfallen when we say two hours may be an hour too long. In fact it takes us two hours just to walk over Totleben’s deeply melancholy creation, most of it buried far underground. It is a relief to find refuge in the long grass of a hilltop concealing the “medieval” gate and to look out over the Cimmerian Bosphorus to the sliver of island called Tuzla. Our guide insists on one last leg through the long grass to show us the “secret” way into the creepy castle.

On then to more subterranean discoveries. The Tsarskij Kurgan, a magnificent fourth- century-bc royal Scythian burial mound, conceals a colossal vaulted chamber. Even in the 1840s, Koch complained that all of Kerch’s Scythian gold was ending up in St Petersburg.

Fortunately, we are spared the limestone mines under the 40ft Soviet statues marking the heroism of the 13,000 Russians who died there in the Second World War – the attraction is closed. But we are able to climb the walls of the Ottoman fortress of Yenikale, which feels quaintly lightweight. Next to the bus station is another royal Scythian tomb, the Melek Çeşme Kurgan, large but less memorable than the Tsarskij. We end the day with satisfying salted herring and vodka at Fishka (where a shot of superior vodka costs less than a postage stamp) before tackling the Mithridates Steps.

Day 7 Kerch

As we walk to the food market on a sunny day, Kerch is transformed, just as our own Bosphorus can be. The streets retain a tsarist flavour – the police station is very handsome. And the market is full of wonders: splendid pickles, stacks of ingeniously displayed salted herring, delicious doughnuts.

Back on the steppe, we pause at the remains of ancient ramparts that seem to run from the Sea of Azov all the way to the Black Sea, protecting Kerch’s hinterland from the west. Who built this colossal wall? Who had the manpower? It appears on no map, but it does have a name, the Tyritake Wall. The two Sashas then whisk us north to strange Kazantip, a cape jutting into the Sea of Azov, with rocky coves, cattle grazing among the rocks, and endless beaches. To the west is the “Russian beach”, with hotels, soft, silty sand and rusting fishing boats. The “Tatar beach”, to the east, has sand of the purest white finely crushed seashell, and is virtually deserted. No contest as a place to swim. Inexplicably, walking on seashell sand fills your feet with joy.

Out of season Kazantip and its treeless nature reserve have a wild beauty. Nodding donkeys are the only sign of habitation.

In summer it may be hell. The Soviets built a city to house workers from the nuclear power station there, but did not finish the station itself, which in the 1990s became a magnet for electronic music aficionados. Their “non-festival” has moved to Yevpatoria.

Arabat is reached by a long dusty road that slices through vast fields edged with poplars. The Ottoman castle is surrounded by rust-red salt flats on one side and blue sea on the other.

Feodosiya, once a sizeable port, is reassuringly urban, with its railway following the promenade. We reject the Soviet-style Lidia Hotel, in favour of a slightly damp room in a guesthouse with a pretty courtyard behind the artist Ivan Aivazovsky’s palatial museum. After a quick tour of the house, where we admire his vast seascapes, some tempestuous, others moonlit and still, we hope for lunch at the flamboyant Stamboli Dacha, but it is deserted, so we make do with coffee. In the evening we drive up to the fortress of Kaffa and explore the strange district of Quarantine and, in its shadow, the old town with its pretty Armenian church, a 17th-century mosque and Aivazovsky’s grand tomb. It feels rather French provincial.

Dinner is hard to find out of season. We finally chance on a dark but busy place under the trees next to the station and are served a tureen of excellent Ukrainian beef stew.

Day 8 Feodosiya

The seaside house of the symbolist poet, painter and pacifist Maximilian Voloshin makes a visit to Crimea worthwhile in itself. Some ten miles from Feodosiya, in the beautiful bay of Koktebel, the house stands in a garden a few steps from the beach.

Up a broad flight of wooden stairs outside is Voloshin’s double-height studio with tall arched windows and views of the sea. A raised alcove creates an intimate space for sitting and reading. Book-lined stairs lead up to a gallery. The whole thing is enlivened by Voloshin’s paintings, paints, books and objets. For such a large man he produced extraordinarily delicate watercolours. The place feels both serene and creative.

The medieval fortress at Sudak is much vaunted for its ramparts, and the view from the Consul’s house at the top is spectacular, though it is rather dominated by the ugly town growing up round the citadel.

The Izmir Restaurant down below is closed, the perfect excuse to head back, on our way to Simferopol, to our favourite roadside café, Nariman’s, for yet more yantık and mantı with thick yoghurt. We have one more mission, though – our promised return to Karasu Bazar. There we meet the delightful Leninnur (the Light of Lenin), who is tending his sheep below the great oak tree where the Tatars gathered before setting out for war.

In Simferopol, we manage to squeeze through closing doors to see the Ethnographic Museum, with its table of painted dolls dressed to represent the myriad ethnicities past and present that have called Crimea home. Sadly, we are not in time to catch the Gothic silver. Dinner is in the chic Cafe No 1. We are barely compos mentis.

Day 9 Alupka

Sunday is our last day. Where else but back to the subtropical Yalta Riviera to see Alupka – a strangely attractive mixture of Mughal, Tudor and Scottish Baronial? We are hoping to track down other palaces that we have read about. They turn out to be too well hidden. But Alupka is delightful enough.

Mulberries come in an array of hues: black, white, pink, purple; some enticingly sweet, others astringent and healing. As Berrin Torolsan can testify, having grown up with them in her Istanbul garden, all are adored – by man, mallard and pine marten alike. Here she traces the history of this lucious fruit

Thomas Whittemore, the American scholar and philanthropist, was instrumental in restoring the Byzantine treasures of Ayasofya. Robert S Nelson delves into his enigmatic life

The V&A’s Tim Stanley eyes up the Louvre’s astonishing new Islamic offering

Aard Streefland tells the story of the Dutch orientalist Marius Bauer (1867–1932)

As the Sadberk Hanım Museum celebrates the art of embroidery, Min Hogg marvels at the motifs of palaces, fruit and flowers, sea and cityscape, wrought stitch by stitch, to adorn every Ottoman home

The Crimean khans founded their capital in the fertile foothills of the Crimean Mountains in the 15th century. This was the nucleaus of the land known as Cim Tartary. The garden palace of Bahçesaray is a glorious reminder of the khans’ 350-year reign

Dramatic and picturesque, Crimea’s southern coast became a resort for doomed royalty and a refuge for ailing literati

Two ports – Sevastopol and Yevpatoria – rule Crimea’s flat west coast. One was built for war, the other for recreation. Both played a part in the Crimean War

Geonese merchants, a millionaire painter and a symbolist poet brought fortune and fame to the eastern stretches of Crimea’s south coast and its fertile hinterland

Balaklava, Sevastopol, Inkerman, the Valley of Death – in Britain, where the savage toll was so acutely felt, these names still have the power to arouse pride and fury. Algernon Percy travelled to Crimea to visit the evocative battlefields

From the Danube to the Caucasus, conflict raged. The Ottomans were fighting for their territories and their lives, but the full story of their courage is only now being told, says the military historian Mesut Uyar

The war of 1853–56 was a calamitous clash of imperial ambitions. Turkey sustained heavy losses, but without them she might have ceased to exist. David Barchard puts the conflict in context

With its healing brine baths and golden beaches, its wealth and variety of architecture, and its layers-deep history, this resort offers something for everyone – from hedonist to hypochondriac

Yevpatoria in Crimea was the home the young Anna Akhmatova, an icon of Russian literature, who fell foul of Stalin

Like many writers, Chekhov made his way to Crimea to nurse his TB in a milder climate. His two houses, now museums, became magnets for artists. One he left to his sister, the other to his wife.

Philip Mansel on the future Edward VII’s Ottoman expedition

By any standard, Hüsamettin Koçan’s mountain-top Baksı Museum, in the northeastern Anatolian village where he was born, deserves a place among the world’s top ten remote museums.

This silver goblet was one of more than 600 medieval treasures from Central Asia crowding Bonhams’ elegant rooms in Edinburgh for six days in January.

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Araci

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now