Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital Edition

This book reintroduces and reexamines the Seljuk inscriptions from the walls of Sinop citadel. First published at the beginning of the last century, these inscriptions open a window onto scribal, administrative, and architectural practice during an important, formative period of the Seljuk sultanate in the early thirteenth century. 16 inscriptions of Sinop citadel, all made within a five month period in the summer of 1215, allow us a glimpse of the Seljuk elite at work, with aspirations and ideals of state and office mixing and competing with individual and factional rivalries and administrative changes. This book corrects previous published versions, and offers for the first time a reading of the main sultanic inscription, which has been chiselled out. Contributors analyze the Persian verse inscription, the first of its kind from Seljuk Anatolia, and the only known Seljuk bilingual Arabic-Greek inscription.

In addition to an in-depth rereading and analysis of these inscriptions, this book examines their architectural context. This includes the first signed work of Abu Ali al-Halabi, the Syrian military architect who served the Seljuk state, and who later built the well-known Red Tower in Alanya. This book provides a new analysis not only of Seljuk architectural practice based on architectural and inscriptional evidence, it also reevaluates the architecture of the citadel itself. Sinop citadel, one of the most impressive in medieval Anatolia, is redated to the Byzantine era.

With a chapter by J. Crow and contributions by O. Özel, A.C.S. Peacock, A. Saunders, and W.M. Thackston, Jr.

Less spectacular and less touristy than its Mediterranean or Aegean counterparts, most guidebooks dismiss Sinop on the Black Sea as “pretty” but difficult of access, with cold-water beaches and an abandoned prison among its key landmarks. Situated on a picturesque peninsula with natural harbours at Turkey’s northernmost point, Sinop is rich in history, and, as Scott Redford’s excellent new book demonstrates, repays careful study.

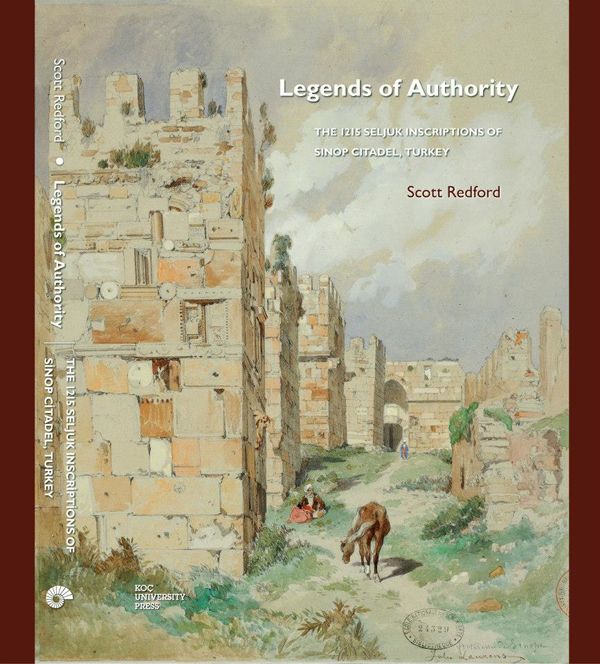

At first glance, Legends of Authority: The 1215 Seljuk Inscriptions of Sinop Citadel might be similarly dismissed as “pretty” but difficult of access. Indeed, the book is handsomely produced, replete with lovely colour images, including Jules Laurens’s watercolours from his travels in 1847. That said, most epigraphic studies are not for the faint-hearted, as their authors narrow their gaze to focus solely on decipherment and classification, based on the vagaries of word usage and letterform in all-but-forgotten languages. But Redford is much more interested in context: not so much what the inscriptions say as what they mean. This drives the narrative structure of the book, resulting in a readable, wide- ranging reassessment of the history and fabric of the city and its implications for the formative period of the Seljuk sultanate.

In 1214, Byzantine Sinop surrendered to the Seljuk sultan ‘Izz al-Dīn Kaykā’ūs, who had military support from the Ayyubids of Syria, as well as from a gaggle of provincial governors, all of whom collaborated in the refurbishment of the citadel. Within the walls and towers are 16 inscribed panels, made within a five-month period in the summer of 1215. The inscriptions provide a sort of gazetteer of who’s who within the power structure at the time, and as the work was undertaken after the sultan had departed, the tensions and presumptions of his heterogeneous entourage are openly expressed in the inscriptional record.

Most of the inscriptions are formulaic: they glorify the sultan for the God-granted victory, then cite the work undertaken (such as the construction of a tower) and give the date, the name of its patron and sometimes that of the scribe who composed the inscription. Of these, 15 are in Arabic, although one is bilingual with Greek, another in Persian. To complicate matters, several are no longer in their original settings, one was intentionally defaced, and another – the most prominent – seems to have been intentionally replaced.

To unravel the manifold meanings and mysteries, Redford steps away from the citadel’s walls to take a broad view, situating the inscriptions within the larger context of local and regional history. To do this, he enlists the aid of a variety of specialists, notably James Crow, who provides a detailed analysis of the well-preserved fortifications.

Most significant in Crow’s contribution is the irrefutable fact that the lion’s share of the fortification system must date to the Byzantine Dark Ages of the 8th–9th centuries, including most of the areas where the Seljuk inscriptions were placed. This reverses the long-standing scholarly opinion that if the inscriptions were Seljuk, the walls must also be Seljuk – indeed, the inscriptions will claim that an emir “built”, but the physical remains indicate he simply “repaired”. The excellent set of architectural drawings not only provide the setting for the inscriptions but also make the book invaluable for the Byzantine specialist. Sinop’s citadel is now among the best-documented Byzantine fortifications in Anatolia.

As Crow and Redford insist, the addition of the inscriptions marks the transfer of power, accompanied by a modest restoration, rather than the construction of the fortification system de novo. Nevertheless, in spite of the hyperbole, the inscriptions can tell us far more. Redford effectively reads between the lines in Chapter 2 (“Power, Display, and Contestation”) to tease out the nuances of the inscriptions, both individually and collectively. While attributing the work to different emirs, the placement, visibility and length of the inscriptions are hierarchical, an expression of the pecking order among the Seljuk elite, with the sultan and the military governors given pride of place, above various ranks of emirs. Taken together, they mark the citadel symbolically as a place of authority.

The use of language can also be instructive: Persian, not Arabic, was the administrative and literary language of the Seljuks, and the many mistakes in Arabic suggest the scribes were not native speakers. Persian inscriptions are exceptional in Anatolia; the single example at Sinop, which belonged to the powerful emir of Malatya, is both poetic and replete with royal and palatial associations. Analysed in an appendix by ACS Peacock, it seems to represent an act of hubris by the emir, who must have played a major role in Sinop’s refortification. On the other hand, the Greek of the bilingual inscription seems to be addressed to a local, recently conquered audience. While repeating the substance of its Arabic counterpart, it is more specific as to the conditions of the conquest and is positioned facing the town.

Within the Arabic inscriptions, Redford notes many scribal practices comparable to manuscript texts, such as angled lines or vegetal or floral ornament, as well as unusual phrasings. He identifies four different scribal hands, one of which may be associated with Ayyubid Syria and seems to be associated with the work of Syrian architects. Unlike many of the Arabic inscriptions, the grammar is flawless. Thus, in addition to the jockeying of the powerful, we get a sense of the heterogeneity of the workforce, both masonic and scribal.

Perhaps most fascinating in Redford’s reconstructed narrative is Badr al-Dīn Abū Bakr, governor of nearby Simre, who seems to have been appointed governor of Sinop after the conquest. Three inscriptions belong to him, including the bilingual panel and a late addition of 1218–19. He is also a likely candidate for the defacing of the main sultanic inscription, and the possible perpetrator of “unspecified offenses” against the Seljuk state immediately after the sultan’s death in early 1219. While Redford admits there is no “smoking chisel”, his argument is compelling. The late inscription is visually prominent, written by the same bad epigraphic hand as another Badr al-Dīn panel, anomalously positioned over the entrance to the citadel, where – framed by lions – the main sultanic inscription should have been, and probably originally was.

As Redford reconstructs the events, Badr al-Dīn both usurped authority and issued the Seljuk equivalent of a damnatio memoriae against Sultan ‘Izz al-Dīn Kaykā’ūs, destroying one inscription and replacing another with a backdated panel. Never mind the fact that it’s too small for its setting and badly written.

What became of bad, bad Badr al-Dīn? We may never know. Within a few years, the Empire of Trebizond reconquered Sinop, and he must have gone the way of other obscure provincial upstarts.

If there is a hero to this story, it is its teller. Redford goes where few epigraphers have dared before, viewing a collection of inscriptions not as an end in itself but as a beginning. With nuance, insight and a little bit of imagination, he brings to life an all-but-forgotten chapter in the history of Sinop by simply reading the writing on its walls.

There is, of course, much more to the book, including a chapter on the near-contemporary inscriptions at Bayburt, which provide useful comparisons; a meticulous catalogue of inscriptions; and additional commentaries in the appendices by WM Thackston Jr and Oktay Özel. Taken together, Redford combines a compelling tale of contestation and display for the general reader with the authoritative documentation that good scholarship demands. In short, both Sinop and Legends of Authority are well worth a visit.

Robert Ousterhout teaches Byzantine art and architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His book ‘John Henry Haynes, A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881–1900’ is available from cornucopia.net at £22.95

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now