Buy or gift a digital subscription and get access to the complete digital archive of every issue for just £18.99 / $23.99 / €21.99 a year.

Buy/gift a digital subscription Login to the Digital Edition

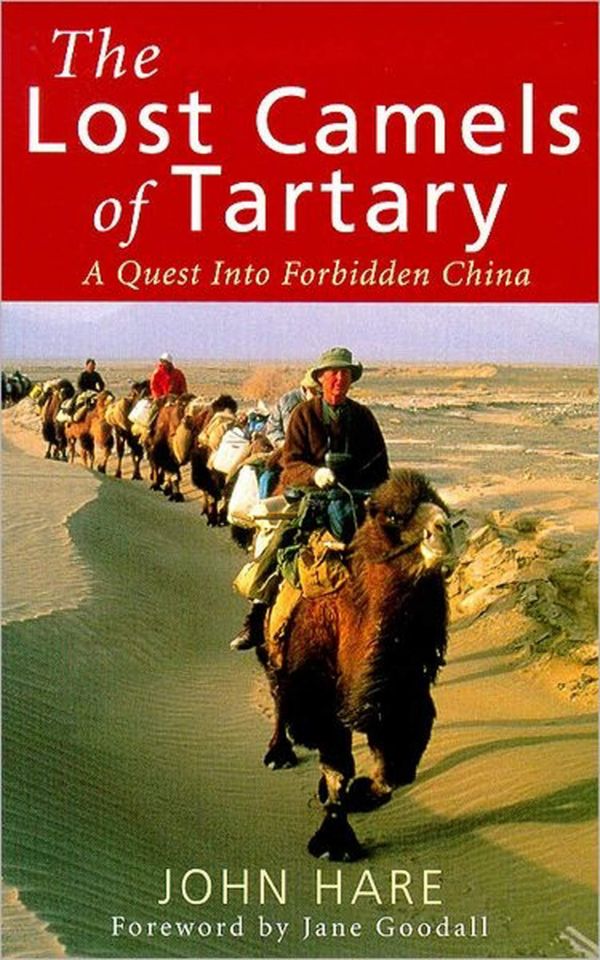

A Quest Into Forbidden China

The Lost Camels of Tartary tells the remarkable story of John Hare’s four journeys into the hostile environment of the Mongolian Gobi and Gashun Gobi deserts, searching for evidence of the survival of the wild Bactrian camel, one of the world’s rarest animals.

Entrusting his life to a colourful cast of companions - an unreformed poacher and a murderous driver among them - he braves bandit attacks, ferocious sandstorms and a missing caravan of domestic camels, shares a wild camel’s first few hours, tracks the equally endangered Gobi bear and happens upon Tu-Ying, ancient outpost of the lost city of Lou Lan. In the process, Hare and his team of scientists brought worldwide attention to the plight of the Bactrian camel, and persuaded the Chinese authorities to establish a 107,000-square-kilometre nature sanctuary in a former nuclear test area to save the camels from illegal hunting and mining.

A compelling account of desert adventure and wildlife conservation in one of the world’s last great wilderness, The Lost Camels of Tartary is a classic record of modern-day exploration.

‘This terrific tale, with its happy ending… serves a wider purpose… To ensure the survival of a large, rare species of mammal also protects the area as a whole.’

Literary Review

‘One of those quests that sounds preposterous but which becomes increasingly compelling thanks to the strengths of Hare’s exuberant narrative.’

Times Educational Supplement

The sceptics held little belief in the concept of a separate species of wild double-humped camel. “Silk Road runaways” or “domestic Bactrian camels gone feral” were the prevailing views. Comparisons were made with the half-million feral dromedaries in Australia that had been released or escaped into Australian deserts and thrived.

Although some had open minds, many heads were shaken when, in 1993, I undertook an expedition into Mongolia’s Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area “A” (GGSPA “A”) to research what I later learnt was the wild camel, a creature very different from the domestic Bactrian. I went with a team of Russian scientists who, in the prevailing chaos of the Soviet Union’s demise, were short of funds. I had managed to get together the $2,000 they required to secure myself a place in the team, but not before I had resolved a tussle with the late Professor Sokolov, who was concerned at my lack of any scientific qualification. He was persuaded I could be their wild Bactrian camel expert when he learnt that many years earlier I had worked with camels in Northern Nigeria.

After this successful expedition I came to the conclusion that the wild Bactrian camel might be a different species. I based my new belief on one important fact. The Mongolian language has a separate name for the wild double-humped camel – havtagai. And havtagai means “flat head”.

For many years I have been an admirer of the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, who during the early years of the last century filled in many blank spaces on the map in today’s Chinese province of Xinjiang. Having read many of his books, I was later to criss-cross his tracks in Lop Nur – that waterless, barren and hostile wilderness which is today almost the last redoubt of the wild camel in China, and which since 1955 has been used by China to test atmospheric and underground nuclear weapons.

In 1907, Hedin shot two wild camels in Lop Nur, returned with their skulls to Sweden, and in a Swedish scientific publication meticulously illustrated their skulls, giving precise dimensions. The Mongolians were right. Unlike the domestic Bactrian camel’s skull, which is convex, the wild camel’s skull is flat.

It was not until 2008 that the concept of a wild Bactrian camel was finally laid to rest. Over a period of five years, the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, under the inspired leadership of Dr Pamela Burger, undertook genetic tests on wild camel samples sent in from habitats in both China and Mongolia. Blood, hair and bone DNA were scrupulously tested. The results vindicated both the Mongolians and Sven Hedin. The wild camel was pronounced to be a new and separate species of camel, which separated from any other known form of camel over 700,000 years ago. No longer was it to be called Camelus bactrianus ferus – but simply Camelus ferus, as confirmed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which organises and approves the Red List of threatened species. It is as different from the domestic Bactrian camel as we are from the chimpanzee.

The intense cold of the Central Asian ice age triggered the evolutionary development of two fat-filled humps as an emergency food supply. Indeed, it could be the ancestor of all camels. It is a little-known fact that the wild camel’s ancestor, a foot-high camelid, originated in the Arizona desert. There is a wonderful display of these humpless camelids in the Natural History Museum in New York. Over the millennia some of these Arizona camelids made their way south (appearing on the eight-mile-long prehistoric mural just discovered in the Amazon rainforest in Colombia), and the evolutionary results are the llama, alpaca, vicuña and guanaco, which live there to this day. Others headed north – a giant camel has recently been found embedded deep in Arctic ice in Canada – but most crossed the Bering Strait and then headed south.

Once the more clement Middle East was reached, two humps were no longer required and mutated into one – the single-humped dromedary had evolved from the double-humped camel. Indeed, if you look at the week-old embryo of a dromedary you will see the remnant of a second hump.

Where does the extant wild camel in Lop Nur and Mongolia fit into this evolutionary cycle? No one knows for certain but, given that it separated from any known form of camel over 700,000 years ago, it could be the ancestor of all camels – both the one-humped and the two.

Cornucopia subscribers can read this article in full in the digital edition.

Help to safeguard the future of the critically endangered wild camel by donating to the Wild Cameil Protection Foundation. The WCPF is the only foundation in the world solely committed to protecting the critically endangered wild camel, and its rare desert habitat in the Gobi deserts of China and Mongolia. The WCPF has established a successful wild camel breeding centre in the Great Gobi near where the last wild remnant population of wild camels live, but a second centre is urgently needed. You can contribute to a crowd funding appeal to raise £75,000. You can also buy a limited-edition print of The King of the Gobi, the portrait of a wild bull camel, signed by the artist, Charlotte Williams (44 x 54cm plus border, £220 + p&p).

Watch A Perfect Planet, David Attenborough's new BBC series, which you can see for free in the UK. Outside the UK, see it from Amazon. The wild camel features in Episode 3.

Buy the book: John Hare describes his early expeditions into Lop Nur in ‘The Lost Camels of Tartary: A Quest into Forbidden China’, with a foreword by Jane Goodall (Little, Brown, £10.99). Order from cornucopia.net/wildcamels.

All proceeds go to the WCPF.

Mongolia's people and landscapes also feature in the new Cornucopia book, The Land of the Anka Bird. See below for related issues of Cornucopia.

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $23.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now