Exactly 150 years ago, on June 5, 1870, Istanbul’s Italian opera house, the Naum Theatre, burnt to the ground in the great fire of Pera which ravaged a large section of the neighbourhood from Taksim to Galatasaray, including the British Embassy. Fanned by strong winds, the theatre’s ashes were scattered as far as Yeşilköy, on the Sea of Marmara, carrying with them charred pieces of stage scenery and remnants of the great proscenium curtain. (Above, fleet-footed firemen rush gamely to the scene, but there was little their waterpumps could do, from Harper's Weekly, 1870.)

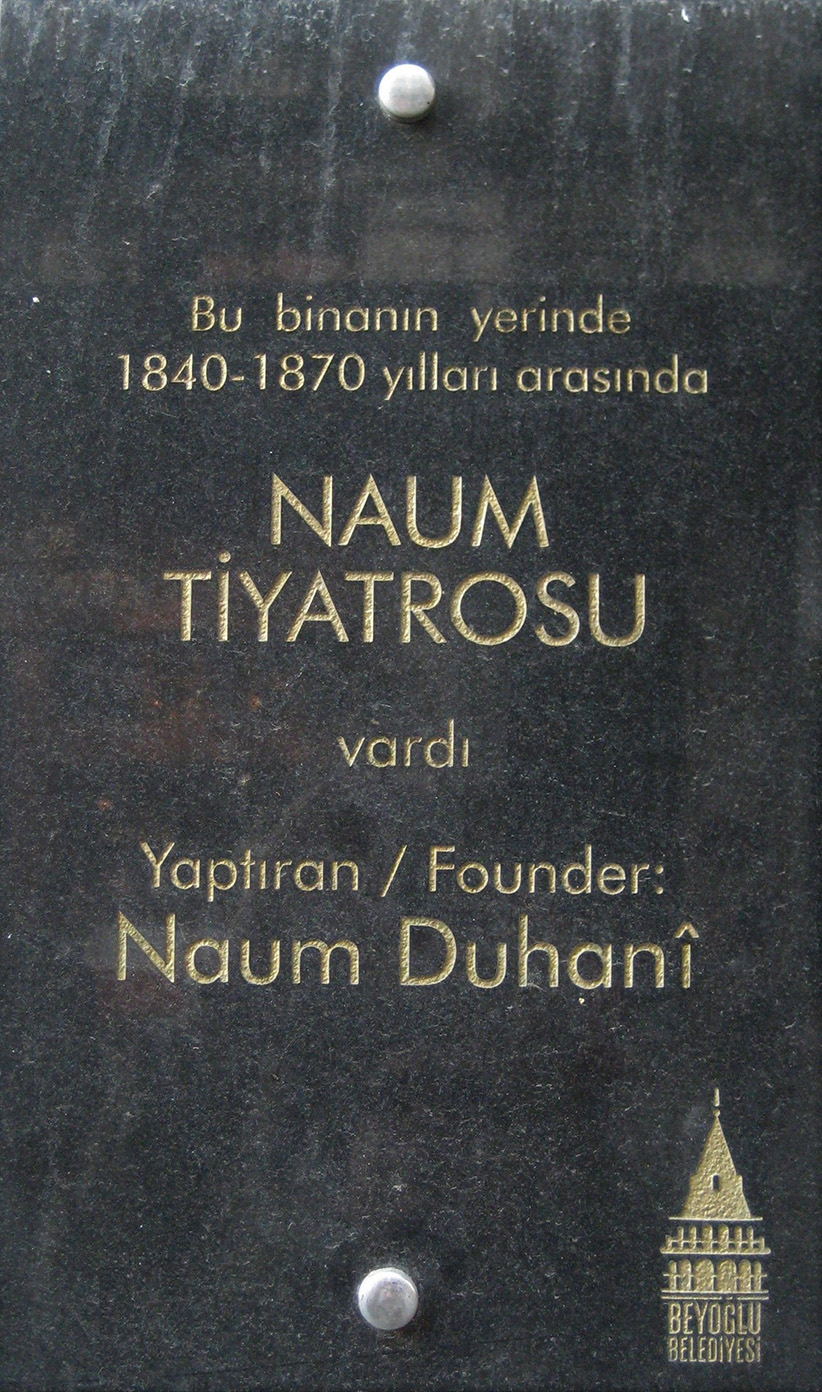

It was a lamentable sight, widely reported in the world's press, but not an unusual tragedy in the history of Pera, and the theatre had already been destroyed once before in a fire in 1847, the year Franz Liszt visited Constantinople. But this time it truly was the end for Pera’s Italian opera house, through whose doors had passed so many famous artists, conductors and members of royalty, including sultans and emperors. With no prospect of rebuilding for the second time, the proprietors, the Naum family, fınally gave up the land, and within a few years a spacious, modern shopping arcade with flats arose in its place. Originally named Cité de Pera, it would evolve into today’s lively Çiçek Pasajı on İstiklâl Street, full of bars and restaurants. Barely noticed by the general public in the hustle and bustle of the main street, a commemorative black marble plaque with gilt lettering, near the entrance, pays homage to this lost establishment.

A plaque at Beyoğlu’s Çiçek Pasajı commemorates the Naum Theatre and its founder. The first theatre burnt down in 1847, the second even more splendid one – designed by William James Smith, the architect of the new British embassy – in 1870

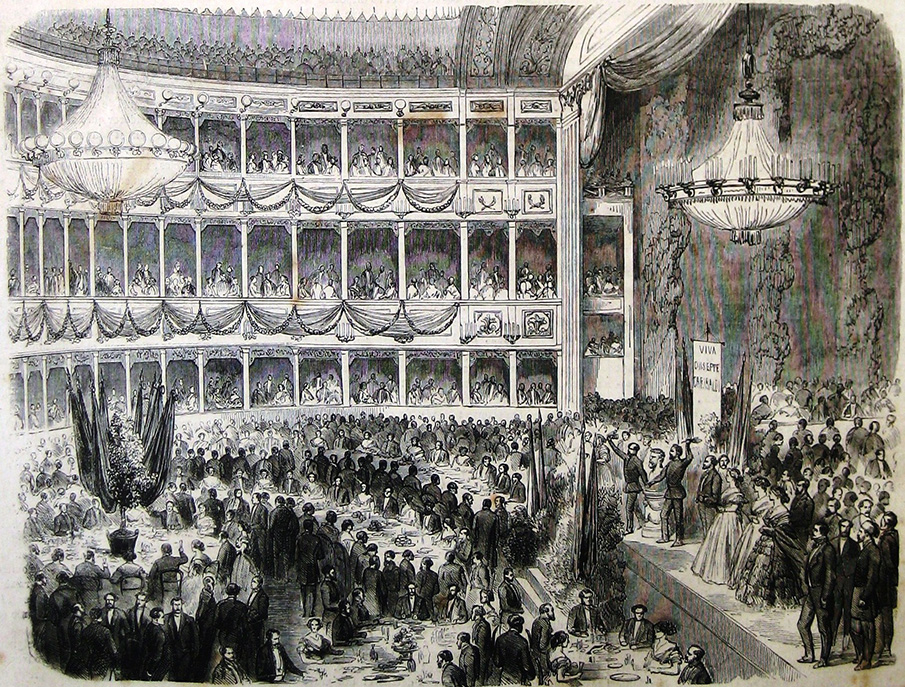

On November 4, 1848, the excitement had been tangible when the Naum family’s sumptuous new opera house, run by the Aleppine brothers, Michael and Joseph, and built to specification by the British architect William James Smith, opened with a performance of Verdi’s Macbeth, conducted by none other than Angelo Mariani, a close personal friend of the composer. The new theatre, with two tiers of boxes and a gallery, was spacious and modern. Its interior was painted white, with gold reliefs featuring large medallion portraits of famous European composers on the auditorium’s ceiling, which encircled an impressive 42-candle chandelier, manufactured in London. For the sultan and his family there was a richly decorated imperial box with a private street entrance. Gas lighting was installed in 1857 and five years later another tier of boxes was added, bringing the audience capacity to 1000. Among diplomats, Ottoman bureaucrats and the leading merchants of Pera, in the audience that first evening was Giuseppe Donizetti, the eldest brother of the famous opera composer, who in a letter to a friend in Italy described the opening as ‘a great triumph for everyone involved’.

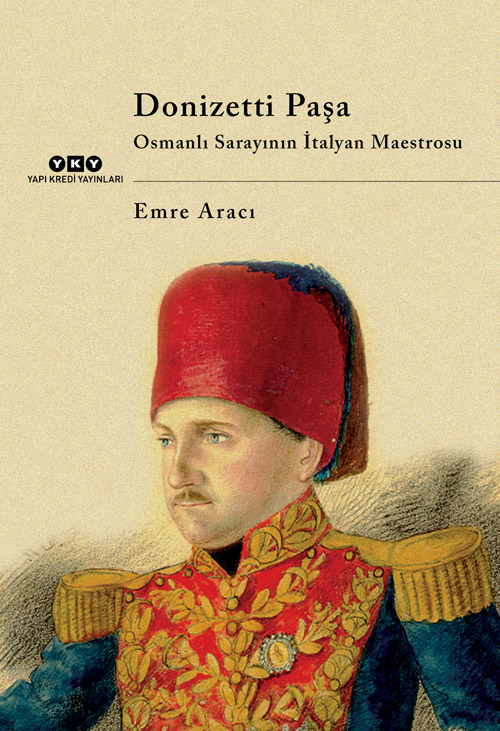

Emre Aracı’s book on the maestro pasha, Giuseppe Donizetti, brother of the opera composer and bandmaster to the Sultan

On the invitation of Sultan Mahmud II, Donizetti Pasha had been living in Constantinople since 1828 as instructor-general of the Imperial Ottoman Military Music School and was among the advisers of the Naum Theatre. He was also instrumental in introducing his brother’s operas to the Turkish court. On one such occasion, when Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Belisario was performed at the apartments of the Valide Sultan, the mother of Sultan Abdülmecid, The Times of London reported – on February 17, 1843 – that ‘the ladies listened very earnestly during the performance, and perused the books [libretti] with great attention. The sympathy of one was strongly excited by the appearance of blind Belisario, and she became so moved by the representation of his distress, that she started up suddenly, and with an expression of pity threw a purse full of gold at him.’ A century later, Leyla Gencer (1928–2008) – La Scala’s ‘Diva Turca’ – would be celebrated for her Donizetti heroines. Here she performs in the finale of Belisario in a 1969 performance (be sure to have your bags of gold – and hankies – ready for the final magnificent note):

Operatic life in Istanbul, however, was not always known for such benevolence. Tempestuous rivalries between leading sopranos were not uncommon, dividing audiences into distinct camps and at times leading to serious fighting in the auditorium – so much so on one occasion in 1851 that a murder was committed during a performance after scuffles broke out between rival supporters of two leading sopranos, Marcella Lotti and Rosina Penco, resulting in the temporary closure of the establishment.

The Naum Theatre in its heyday, from the pages of L'Illustration, April 19, 1862. The Prince and Princess of Wales and the Austrian emperor Franz Josef all attended gala performances here in 1869 as guests of Sultan Abdülaziz

Despite such troubles, the Naum Theatre continued to dominate the cultural life of the city, with the brothers Naum regularly recruiting famous artists from Italy each season for the benefit of Pera society. When La Traviata was premiered in Istanbul in the 1856–57 season, for instance, Violetta was sung by Fanny Salvini-Donatelli, for whom the role had originally been created by Verdi at Venice’s La Fenice. In 1852, Anna Caradori – known to the audiences of La Scala and Covent Garden – appeared at the Naum Theatre, to the delight of the Pera audience. In later years Teresa Stolz, the great Verdi champion, sang there to great acclaim. On other occasions Adeliade Ristori, the famous Italian tragedienne, starred in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, while the French soprano Adelina Murio-Celli charmed audiences in Norma, and Carlotta Patti appeared with Pablo de Sarasate. One of many famous virtuosi to perform at the theatre, Henryk Wieniawski played Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, and the company also featured a resident corps de ballet. In the autumn of 1850 Gustave Flaubert, passing through Constantinople, saw Lucia di Lammermoor here and would later incorporate a scene from the opera into the central plot of his celebrated novel Madame Bovary. The theatre was also a centre of much socialising, gossip and spectacle, with ladies dressed in glittering costumes arriving in sedan chairs carried by two servants – not only for performances, but also to attend grand costume balls, held annually during the Mardi Gras season before Easter.

During the Crimean War, the audience swelled with European officers and soldiers on their way to and from the front, along with journalists and writers. Among these was Eustace Clare Grenville Murray, second son of the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, who contributed regularly – under the pseudonym The Roving Englishman – to the weekly Household Words magazine, edited by Charles Dickens. ‘I cannot say that the opera of Pera absolutely claims a visit from the connoisseur. There is an unhealthy smell of dead rats about it; a prevailing dampness and dinginess; a curious fog; a loudness; a dirtiness, which induces me generally to prefer an arm chair and a dictionary, a cup of tea and a fire,’ he wrote in one of his reports from Constantinople. He went on to ridicule an establishment where ‘an English autumnal prima donna’ was ‘tearing one of Verdi's operas into shreds, and screaming in a manner which is inconceivably ear-piercing’ (Household Words, no: 253, January 27, 1855).

Despite such reports, the Naums relentlessly carried on, and soon after the end of the war the Italian maestro Luigi Arditi came to Constantinople as the theatre’s new musical director for the 1856–57 season. He marked his stay in the city by composing a choral ode, ‘Inno Turco’, in the Ottoman language and dedicated to Sultan Abdülmecid, which was sung by the artists of the theatre at Dolmabahçe Palace before the sovereign and his entourage.

Emre Aracı is the author of ‘Naum Tiyatrosu: 19. Yüzyıl İstanbul'un İtalyan Operası’ (The Naum Theatre: A 19th-century Istanbul Opera House), 2010, available (in Turkish) from Yapı Kredi Yayınları:

He tells the remarkable story of the opera house in a new youtube recording here: