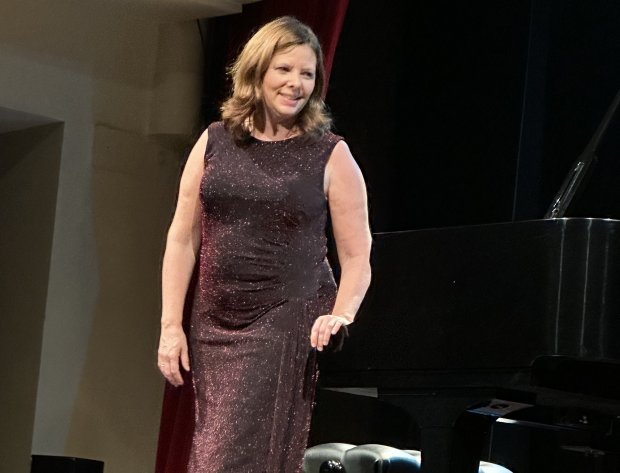

On November 1 I made another visit to Istanbul's Notre Dame de Sion French Lycée in Harbiye to attend a concert by the Belgian pianist Éliane Reyes. This was the second of the musical events organised by this school that I have recently attended, the first having been a concert to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic.

Éliane Reyes was a child prodigy who performed with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam when she was only eleven years old. She received her training at the Royal Conservatoire in Brussels, the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin, the Mozarteum in Salzburg and the Paris Conservatoire (the ‘Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique’), where she was taught by Brigitte Engerer and Jacques Rouvier. Currently a Professor of Piano at both the Brussels Royal Conservatoire and the Paris Conservatoire, in 2016 she was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. In addition to giving recitals as a soloist, she also performs regularly as a chamber musician.

Mme Reyes’ speciality is the music of French composers, and her programme on this occasion was made up of works by composers who were either French themselves (such as Ravel and Debussy) or who had a strong connection with France – such as Chopin, whose father was French, and Liszt, who lived in Paris for five years in his youth and later formed a relationship with a French countess.

She began with a series of Chopin waltzes, the first of these being Opus 42 in A flat major. This was followed by the two from Opus 64 (No 1 in D flat major – the ‘Minute Waltz’ – and No 2 in C sharp minor) and the two from Opus 69 (No 1 in A flat major, nicknamed ‘L’Adieu’, and No 2 in B minor). Though I appreciated the sensitivity of Mme Reyes’ phrasing, I found her rendition of these waltzes rather hurried on occasions. The ‘Minute Waltz’, in particular, suffered from being taken too fast, and some of the top notes did not sound. Though there have indeed been competitions to see who can play this piece the fastest, I see no reason why pianists should play it at top speed in concert performance, thus sacrificing its subtleties. In the C sharp minor, I thought her control over the underlying rhythm in the wistful first theme was somewhat unsteady; however, I found the thoughtful ending she gave to the next piece – ‘L’Adieu’ – very pleasing.

It was only in the next two waltzes – the A flat major and B minor from Opus 69 (both of these being ‘opus posthumous’ or ‘op. posth.’, meaning that they were published after the composer’s death) – that Mme Reyes finally seemed to settle down and relax. This was a good thing, as Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu in C sharp minor, the work she played after these last two waltzes, is a real tour de force. This piece, composed in 1834, was published in 1855 (after the composer’s death in 1849) despite his instruction that none of his unpublished manuscripts be published. Here, Mme Reyes at last showed her true colours, managing the difficult running passages and arpeggios with impressive technical skill.

At this point, I would like to present recordings of performances of two of the works I have mentioned so far – the Waltz in C sharp minor, Opus 64 No 2, and the Fantaisie-Impromptu. Firstly, the Waltz in C sharp minor in two performances – by renowned Chopin interpreter Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982, as a representative of the classical school of pianism) and by the contemporary pianist Khatia Buniatishvili, who takes a more ‘liberal’ approach to variations in tempo. Their interpretations are vastly different, though both ignore the fact that the composer actually marked the first theme tempo giusto, which means ‘in correct time’. However, it would be a stoical pianist indeed who refrained from adding a dash of rubato to the mix in order to bring out the piece’s emotional flavours.

Secondly, here is the Fantaisie-Impromptu played by Daniil Trifonov in what looks like a deserted warehouse, with excerpts from an imagined encounter in Chopin’s love life. Trifonov’s performance certainly has emotional commitment, but do skip the visuals if you find them excessively fanciful.

Mme Reyes followed Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu with his Ballade No 1 in G minor, another roller-coaster. The Wikipedia article informs us that this Ballade, completed in Paris in 1835, is one of a series of four that are ‘some of the most important and challenging pieces in the standard piano repertoire’. As for the name ‘Ballade’, the article has this to say:

Chopin used the term ‘ballade’ in the sense of a balletic interlude or dance piece, equivalent to the old Italian ballata. However, the term may also have connotations of the medieval heroic ballad – a narrative minstrel song, often of a fantastical character. There are dramatic and dance-like elements in Chopin’s use of the genre, and he is a pioneer of the ballade as an abstract musical form. The four ballades are said to have been inspired by a friend of Chopin’s, the poet Adam Mickiewicz.

Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist and essayist of a decidedly Romantic turn of mind who is regarded as a national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. He met Chopin while living in Paris in the early 1830s, and the composer became one of his closest friends. Indeed, in the winter of 1848-49 (when Mickiewicz was depressed over the withdrawal of an offer of a university post in Kraków) Chopin visited him several times – despite being terminally ill himself – to soothe the poet’s nerves by playing the piano to him. Wikipedia again:

Mickiewicz was born in the Russian-partitioned territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was active in the struggle to win independence for his home region; in consequence, he spent five years in exile in central Russia. In 1829 he succeeded in leaving the Russian Empire, and (like many of his compatriots) lived out the rest of his life abroad. He settled first in Rome, then in Paris, where for a little over three years he lectured on Slavic literature at the Collège de France. An activist who strove for a democratic and independent Poland, he died, probably of cholera, at Istanbul in the Ottoman Empire, where he had gone to help organise Polish forces to fight Russia in the Crimean War.

(In fact, the house in which Mickiewicz died is located in Tatlı Badem Sokağı, Dolapdere, a non-representational stone’s throw from the ‘Arter’ gallery of modern art.)

Earlier, I described the Ballade No 1 as a ‘roller-coaster’; on second thoughts, however, I think it might be more accurate to characterise it as a ‘bipolar romp’. When the piece was first heard in the sedate salons of Paris, the ending (in which the pianist’s hands perform a chromatic scale in octaves in contrary motion, the surprisingly extreme dissonances emphasised by acciaccaturas) must have been a slap in the face – the kind of challenge to musical convention that might, perhaps, have been expected of a man who had formed a friendship with firebrand Adam Mickiewicz. (The Poles were certainly in rebellious mood during these years: in 1831, four years before the composition of the Ballade, they had risen in revolt against their Russian overlords in the – ultimately unsuccessful – ‘November Uprising’. This event is commemorated in Chopin’s Etude No 12 in C minor, subtitled the ‘Revolutionary’.)

Back to the concert. By this point Mme Reyes was going from strength to strength, and her rendition of Ballade No 1 was a riveting one that did full justice to the piece’s histrionic extremes. Her playing here, as indeed it had been in the Fantaisie-Impromptu, was of such perfectly-controlled evenness that it was a treat to listen to, and the con fuoco coda (in which the composer hard-heartedly requires the pianist to run an extra mile at breakneck speed after some already exhausting bravura passages) was executed with no sign whatsoever of strain. I only wish I could share a recording of her performance with you, but instead I will opt for one by Murray Perahia.

The second half of the concert on November 1 had a decidedly watery feel to it. The first two works we heard after the break were Ravel’s Jeux d’eau, written in 1901 and inspired by Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este (1877), and the aforementioned Liszt piece itself.

At the time when Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) wrote his Jeux d’eau, he had been expelled from the Paris Conservatoire for failing to win any prizes; he was, however, permitted to attend the classes of Gabriel Fauré, his former teacher of composition (who thought highly of him), and the piece is dedicated to his mentor. I cannot help but quote Wikipedia once again.

Jeux d’eau has a claim to being the first example of impressionism in piano music. The piece is known for its virtuosic, fluid and highly evocative nature, and is considered one of Ravel’s most important works for piano. It is characterised by fast, shimmering and cascading piano figurations that are meant to evoke the sound of flowing water. The overall atmosphere of Jeux d’eau is one of lightness, playfulness and sensuousness, and the piece is often described as a musical depiction of the joy and beauty of nature.

Notwithstanding the fact that the audience at its first performance in 1902 found it ‘cacophonic and excessively complicated’, Jeux d’eau eventually became (in the words of Ravel’s biographer Arbie Orenstein) ‘firmly established as an important landmark in the literature of the piano’. The following performance is by the Hungarian pianist György Cziffra (1921-1994), a virtuoso of quite astonishing technical proficiency. Mme Reyes’ website tells us that her encounters with Cziffra at the age of ten, and which led to her being accepted as a pupil at the foundation he had set up in Senlis (near Paris), were a major turning point in her career.

György Cziffra’s life was not without its ups and downs. Born into a poor family of gypsy musicians in Budapest, he began playing the piano by imitating the pieces his sister played when she was practising (though he could not read music). He then learned to reproduce on the piano, and improvise upon, tunes sung by his parents, and this skill eventually enabled him to earn money by improvising on tunes from popular music at a local circus. His training as a classical pianist began in 1930, when he entered the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest as a pupil of Ernst von Dohnányi; afterwards, he embarked on a career as a concert pianist.

Hungary was, of course, on the German side in the Second World War, and in 1941 Cziffra was drafted into a unit that was sent to fight the Russians; however, he was captured by Russian partisans and held as a prisoner of war. Having survived his wartime privations, he subsequently earned a high reputation as a jazz pianist, playing with a group that toured Europe. In 1950 he made an unsuccessful attempt to escape from Russian-occupied Hungary, and was first imprisoned, then sent to a labour camp. During this time, he severely sprained his wrist as a result of being forced to carry 130 pounds of concrete up six flights of stairs. After another – this time successful – attempt to escape from Hungary in 1956, he resumed his career as a concert pianist, being widely admired in Europe and the United States for his formidable technique, though he often had to wear a leather wristband to support the ligaments of his damaged wrist.

Here is a recording of György Cziffra playing Ravel’s Jeux d’eau, with the score.

Eliane Reyes was highly impressive in the Ravel. The evenness with which she had played the running passages in Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu and his Ballade No 1 was even more evident in Jeux d’eau, where her lightness of touch ensured a perfect depiction of swirling, cascading water. This same ability was equally evident in her performance of the next piece – Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este (‘The Fountains of the Villa d’Este’), from Volume III of Années de pèlerinage (‘Years of Pilgrimage’). It is difficult to believe that this surprisingly modern-sounding work – yet another manifestation of its composer’s originality – was written as early as 1877. It was inspired by visits to the Villa d’Este, located in Tivoli, near Rome, where Liszt frequently stayed as the guest of Cardinal Gustav von Hohenlohe. The Cardinal had restored both the dilapidated 16th-century villa and its overgrown gardens (which had many attractive water features), thus making the place appeal strongly to romantic sentiments.

Franz Liszt’s acquaintance with the Cardinal may have been the fruit of his religious connections: in 1865, having suffered the loss of his 20-year-old son and his 26-year-old daughter, he was ordained as a priest. He had always been an idealist, often donating the income from his concert performances to charity, and no doubt these emotional blows further deepened the serious, contemplative side of his personality. (Liszt had planets in all the empathic water signs, with lovely Venus making a harmonious trine to philosophical Jupiter.) And indeed, it is these characteristics that the Hollywood Bowl website brings to the fore in its description of Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este.

While Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este is the progenitor of all pianistic water-music to come (Ravel and Debussy lay decades ahead), its intent goes beyond the musical depiction of the rilling and leaping of waters in fountains. It offers water as the symbolic focus of profound contemplation.

The pianist whose recording of this piece I have chosen to present is once again György Cziffra.

Mme Reyes ended her recital with Debussy’s L’isle joyeuse, ‘Island of Joy’ (1904). Some have claimed that it was written in the summer of that year, while the composer was on holiday in Jersey with Emma Bardac, his new mistress. (Before departing from Paris, Debussy had packed his wife off to her parents, later writing to her from Dieppe to tell her that their marriage was over.) Recently, however, it has come to light that he began writing it before that time, though he may have given the work its final form while on the island. Following its première, at which it was played by the famous Catalonian virtuoso Ricardo Viñes, to whom Ravel dedicated his Oiseaux tristes and Debussy his Poissons d’or, it quickly became a success with the public. (In the photograph in his Wikipedia entry, Viñes is sporting an absolutely wonderful moustache.)

The following performance is by the Québécois pianist Marc-André Hamelin.

After thrilling us with this celebration of the joy of life, and before playing her encore (a slow, sad piece in A minor), Mme Reyes gave a short speech in which she reminded us that November 1 is celebrated in the Roman Catholic Church as All Saints’ Day, and that November 2 is All Souls’ Day, on which by tradition the dead are remembered. She then told us that earlier this year she had lost her husband, who was still in his forties, and dedicated the piece to his memory. This may have made a less-than-upbeat ending to the recital, but everyone in the audience felt a great deal of sympathy and respect for the performer as a result. The applause she received at the end of the proceedings was both fulsome and well deserved.

And so it is time to express my gratitude to the Belgian Consulate for their part in organising the concert, and to Notre Dame de Sion French Lycée for hosting it. They have certainly set a high standard for themselves, and I will be keeping an eye open for any future events at this venue.