After a hiatus caused by a stay in delectable Tameside for the run-up to the festive season, I am back in Istanbul. On Saturday, January 12 I braved the appalling weather (almost as cold, wet and dismal as Manchester in August) to listen to a recital by Freddy Kempf (pictured above) at The Seed in Emirgan, the latest in the Istanbul Recitals series at the Sakıp Sabancı Museum.

Kempf, born in London in 1977 to a German father and a Japanese mother, gave his first concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at the age of 8. Two years later he won the British National Mozart Competition. It was in 1992, however, that he truly came to prominence, winning the BBC’s Young Musician of the Year competition with a performance of Rachmaninov’s Paganini Variations. After failing to win first prize in the 1998 International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow (and attracting a great deal of publicity in Russia, as many thought he should have come equal first), he returned to Moscow the following year for a triumphant series of television broadcasts and concerts, prompting the International Herald Tribune to declare ‘Young Pianist Conquers Moscow’ in a headline. In a review in The Guardian in 2003, it was said that ‘the meteoric success of pianist Freddy Kempf makes it easy to forget he is in his mid-20s. If it is true that an artist's finest years come with age, then the mind boggles at the possibilities.’

Having listened to him on YouTube playing Chopin’s Etudes with all the speed of a striking mamba, and having been reliably informed that one cannot turn on BBC Radio Three these days without hearing Mr Kempf, I had definitely committed the sin of anticipation when I entered the auditorium – thankfully in operation once again after a temporary transfer to a marquee in October. Thanks to blustery Boreas, it was certainly too cold for an al fresco occasion, however much the pianist may have set the nearby Bosphorus on fire with his jaw-dropping virtuosity.

Mr Kempf appeared tense as he walked onstage. “Good,” I thought. “He is taking this concert seriously.” The programme began with Sergei Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No 1, an early work dating from 1909 in which the composer’s late romanticism had not yet given way to the chilling atonality of his mature period. Alexander Carpenter notes that ‘The sonata has somewhat of a stylistic ‘split personality’, sitting on the cusp between the late 19th-century romanticism of Liszt and a somewhat more austere, early 20th-century sensibility.’

Of the three movements the work originally had, only the first was released to the public by the composer, who deemed movements two and three to be just too jejeune. In this I fear he may have been right. There is more than a touch of gratuitous exhibitionism to this work, and one expects more of a sonata than a display of technique overlaid upon a somewhat rigid interpretation of traditional first-movement sonata form. In his diary Prokofiev later noted:

‘That summer I decided to write a long piano sonata. I was determined that the music would be more beautiful, the sonata interesting technically, and the content not superficial. I had already sketched out some of the thematic material. In this way I began to work on the F minor Sonata No 2, in three movements, and wrote a good deal of it in a very short time. It proved to be a more mature work than my other compositions of that period, and for several years it towered above them as a solid opus. Later I discarded the second and third movements, then reworked the first and made it into Sonata No 1, Opus 1. But alongside my serious numbered works, this sonata seemed too youthful, somehow. It turned out that, although it was a solid opus when I was 15, it could not hold its own among my more mature compositions.’

Yes, it is that word – ‘superficial’ – that this work may try to skirt around, but still cannot avoid running into at full tilt. Although Mr Kempf seemed to be devoting a great deal of emotional commitment to it, and indeed gave the piano such a hammering that I was seriously concerned lest it go out of tune, in my view the piece did not merit his contributions to it. At the end of the performance he made a hit with the audience by saying “Teşekkürler!” (thanks) in response to their applause, and by pronouncing the word – which I myself find quite a mouthful, even after 40 years in Turkey – in a way that showed he had obviously practised.

Here is a video of Freddy Kempf playing Prokofiev’s Sonata No 1:

This was followed by a much later work from the same composer – his Sonata No 8, written in 1944 as the third of his so-called ‘War Sonatas’. In comparison with the first, the eighth is a far more heavyweight kettle of… piranha, each one with its teeth lovingly sharpened into points. The contrast with the previous piece was immediately apparent: gone were the romantic flourishes, to be replaced by an ice-cold, brutal atonality in which the occasional concession to a perceptible home key was granted only for the purpose of letting you see the knife in sharper focus as it twisted into your tender nether regions.

My favourite recording is the one by Emil Gilels – who gave the first public performance of the sonata in December 1944 after playing it through to Prokofiev and receiving his corrections, so the pianist is at the very least faithful to the composer’s intentions:

The following rendition by Vladimir Ashkenazy has the advantage of being accompanied by the score:

Boris Giltburg has some interesting things to say about Prokofiev’s Sonata No 8 in the video below. I especially like his description of the first theme of the first movement as ‘a poisonous cold something creeping on the surface… there is definitely no lyricism’, and his comparison of the desolate second theme (which occurs at 03:34 in the Ashkenazy performance) to an abandoned village that has been the scene of a battle. I also agree with Mr Giltburg’s remarks on the sense of detachment that the work gives. Sviatoslav Richter once said of it that ‘… at times it seems to grow numb, as if abandoning itself to the relentless march of time’:

During his recital in Emirgan, Mr Kempf did not spare us any of the ferocity of the very long first movement. In the second, an ostensibly reassuring slow waltz-cum-minuet with an elegantly disturbing too-good-to-be-true feel to it, he gave full rein to the composer’s talent for not-quite-playful lyricism; the poison, this time, was in the fluffy icing on the cake. This movement, the only one to have a readily discernible tonal basis, is marked Andante sognando; the word sognando, which means ‘dreamlike’, neatly sums up the ‘fool’s paradise’ quality of the music. Here the pianist brought out the rich and melodious inner parts with great success.

In the finale it was of course his technique that stole the show. My criticism of this movement – that the lack of any clear tonality outside the iterations of the main themes renders the frenetic atonal meanderings meaningless – is of course directed at the work itself, not the performer. I will concede, nevertheless, that I find the return of the ‘abandoned village’ theme from the first movement (which comes at 24:01 in the Ashkenazy performance listed above) most pleasing. The finale builds up – after an andantino interlude marked irresoluto – to a climax of terrifying heroics. As the last chord-crashes died away I felt that Mr Kempf had, without any doubt whatsoever, earned his ticket to Istanbul.

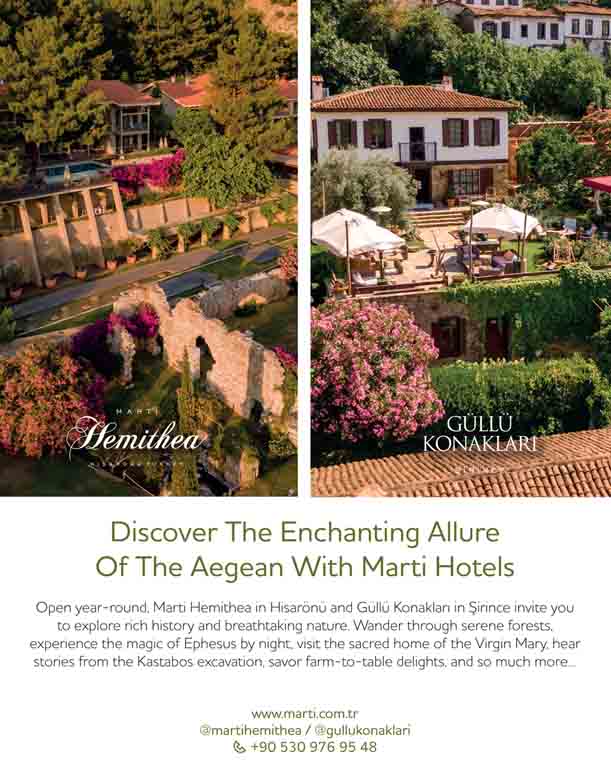

The second half of the recital began with three pieces by Nikolai Kapustin (above), a Russian pianist and self-taught composer born in the Ukraine in 1937 and still going strong – Maşallah! Kapustin studied the piano at the Moscow Conservatory, following which he played jazz firstly with two big bands, then with radio and cinema orchestras. According to his website he ‘turned out to be a classical composer who happens to work in a jazz idiom. He fuses these influences in his compositions, using jazz idioms in formal classical structures’. For serious fans, here is a link to that website.

The pieces Freddy Kempf played to us were Nos 1, 7 and 8 of the flashy Eight Concert Etudes, Opus 40. In the following recording they are played by the composer himself.

The audience got into No 7 in a big way (in the video above, this starts at 16:12), and clapped enthusiastically at its conclusion even though this was not the last item on the Kapustin menu. And I have to say that after the brooding heaviness and brittle frigidity of the Prokofiev, a bit of light-hearted frivolity was not at all unwelcome.

But finally the pianist got down to business once again. Having left the stage briefly at the end of the Kapustin, he marched back on again with determination written all over his face, and did not even wait for the welcoming applause to die down before launching into the tumultuous opening of Rachmaninov’s Sonata No 2 in B flat minor. One can only marvel that any human being is capable of playing this fearsome piece, but it appears some have not been daunted by it. Here, for instance, is a performance by Vladimir Horowitz.

I have been unable to find a video of Freddy Kempf playing this work, so I will content myself with recording the fact that his technique does not seem to me to be in any way inferior to that of Horowitz – even in the matter of ultra-high-speed octaves, for which Horowitz was deservedly famous. Another feature of Mr Kempf’s playing is the excellent gradation of tone: nothing is ever too loud or too soft, and the relative importance of all elements of the accompaniment to the melodic line is always given careful attention.

The Sonata No 2, originally written in 1913, was revised by the composer in 1931. As a description of the work, I cannot better that of Adrian Corleonis:

‘The allegro agitato opening seizes one by the hair with an arpeggiated plunge to the bass, two sharply peremptory chords (announcing the crucial interval of a third), and a falling, wailing figure in the left hand beneath tremolando triplets in the right, giving way to great waves of kinetic nervosité. It is the entrance of a great actor... Rachmaninov’s 1931 revision – the version usually heard – cut 120 bars from the original, pared some of the virtuosic extravagances, and made for more transparent textures. The second movement, following without a break, works melancholy from nostalgic elegy to a fever before a slashing arpeggiated descent brings on the alternately anxious and towering finale – with its snatches of a parodied march – shot through with one of Rachmaninov’s most compelling lyric inspirations confided first in single notes and valorised in the peroration in massive, surging chords before a final virtuoso wash of triumphant sonority.’

The next video has the benefit not only of the score but also of some good programme notes analysing the form of the work (this is available on YouTube): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_lOOYSzoBc

Rachmaninov’s style is a lot more approachable than that of Prokofiev, of course, and the emotionally charged melodies of his second piano sonata (these come after the initial Allegro agitato) were a welcome return to familiar human territory: even after the Kapustin, the effect of Prokofiev’s ventures into the uncharted stratosphere of intellectual abstraction in the first half of the concert had still not quite worn off.

There were quite a few moments in the first movement of the Rachmaninov where it occurred to me how good the music would sound if played by an orchestra, and indeed the composer may have been subconsciously orchestrating what he was putting on paper. In the lyrical second movement it was Mr Kempf’s musicianship, rather than his technique, that aroused my admiration: he played as if his life depended on it, and for this I was – and still am – thankful. It is for occasions like this that one goes to concerts.

Now that I have said such nice things about the pianist, it will come as no surprise that I enjoyed his interpretation of the last movement, too. It was played with confidence and consummate control despite the awesome challenges presented by the score – those rapid-fire repeated chords must leave you with an ache stretching right up both forearms. One last point: Freddy Kempf played everything from memory, proving he had approached his engagement in Istanbul with respect and a sense of dedication. (Are you listening, Alexandre Tharaud?)

But I will retract my sting and save it for another occasion (unlike bees, we wasps can sting as many times as we like, you know). Nothing about this concert deserved even a threatening buzz. Thanks are due to the soloist for giving us his all and holding nothing back, to the current organisers of the Istanbul Recitals, and to the late Mr Kâmil Şükûn for having initiated them. Leaving the auditorium, I walked out into the lashing rain feeling satisfied, benign towards my fellow creatures and at peace with the world, and that surely is what music is about.