Kitsch has a troubled history. The term was initially coined as a response to the proliferation of art forms concurrent with the industrial revolution, and the awareness that mechanical reproduction had caused artworks to lose their aura. What was the meaning of an artwork when it was reproduced thousands of times on picture postcards? Kitsch went on to be derided by modernists as ornamental or decorative, spurious and non-functional, as antithetical to the singular avant-garde artwork as conceptualised by mid-century modernists. Taste was what classified art, excluding the crafty, the mass-produced and the sentimental.

In recent decades, however, such a perspective has been picked apart. The idea of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture has collapsed; the sense that taste classified the classifier as much as the classified has given way to an understanding of how it worked to exclude broader understandings of art. Meanwhile, the globalisation of the world began to unpick the universalist and exclusionary histories on which understandings of art have traditionally been based. The weighty, serious sense of the ‘artwork’ has given way to something far more open, joyful and fun.

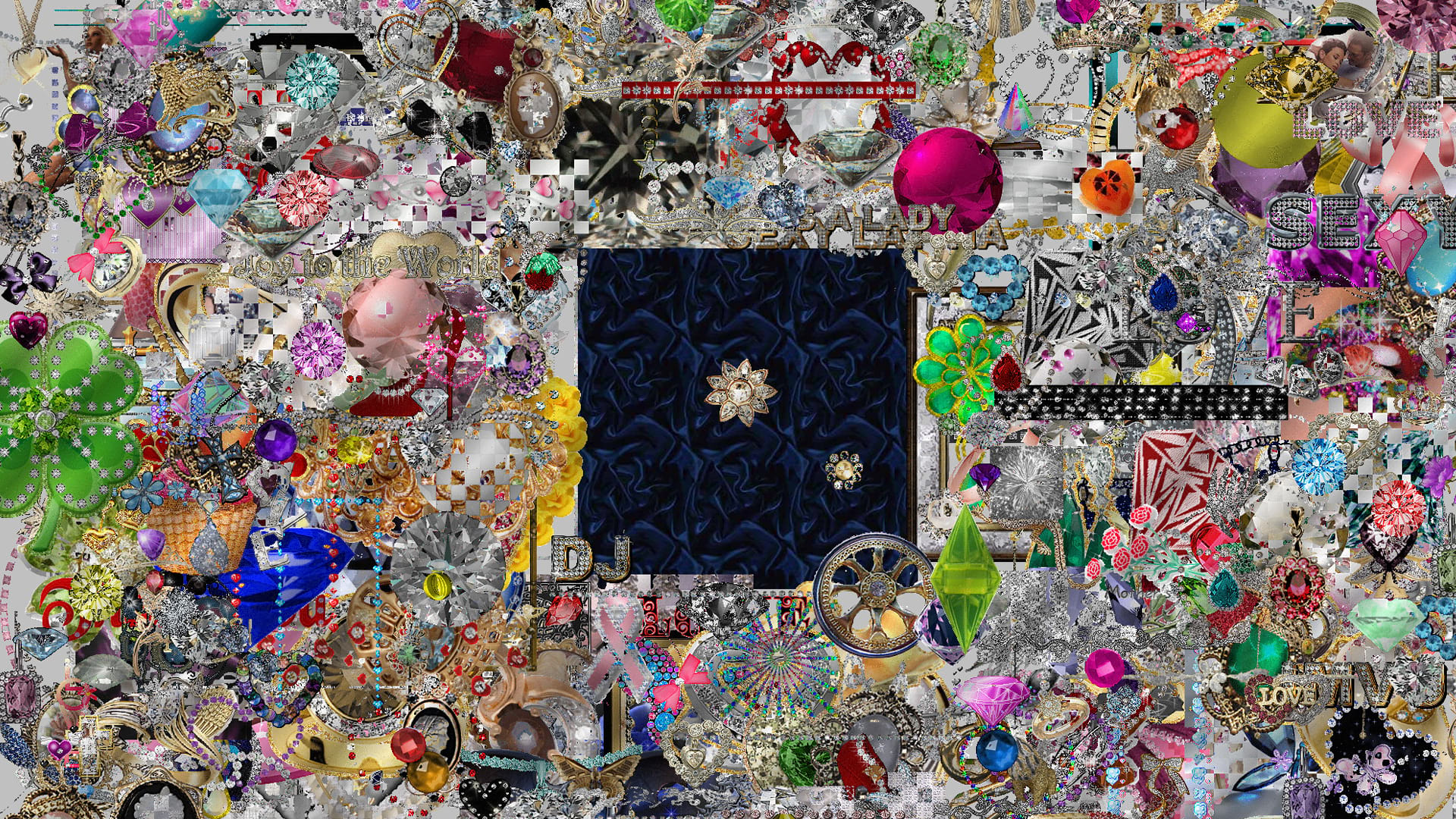

Gemstone GIF: Olia Lialina’s video 'Treasure Trove' is a collage of GIFs on the Blingee platform, which offers users tools to add glitter flowers, hearts, jewels or animated text to their own GIFs

The exhibition A Question of Taste (Zevk Meselesi) (at the Pera Museum until June 6) seeks to contribute to this wider project of re-investigating the meaning of kitsch. Magisterially curated by Ulya Soley, it is an elegant and playful collection of artists who offer a series of different forays into the possible implications of kitsch – as a way of thinking about our globalised world, a means of institutional critique, and an alternative vantage point from which to consider politics.

At the beginning of the exhibition the visitor is confronted by beadwork made by prisoners – a 19th-century tradition that continues in Turkey’s prisons today. These small, personal objects invite us to consider moments of pathos and beauty within the larger prison system.

Juxtaposed against them is Nick Cave’s video of dancers…

…and the sumptuously camp photographs of Pierre et Gilles

The exhibition progresses through the works of Gülsün Karamustafa (above) and Volkan Aslan (main picture, top), inviting us to consider further the local relevance of kitsch. Karamustafa’s work has long dealt with the meaning of displacement and internal migration, objects that gain and lose meaning through transplantation. Volkan Aslan, meanwhile, inspired by the Pera Museum’s famous collection of Kütahya porcelain, has created a strange, baroque collection of figurines and objects that play with the duality of porcelain as both high art and a signifier of the mundane, bourgeois display cabinet.

A still from Farah al-Qasemi’s video Dream Soup

The exhibition moves on to a consideration of our age of digital, and global, reproduction. A series of works explores digital aesthetics in a globalised world. Playing in a pink-carpeted, sweetly scented room, the artist Farah al-Qasemi’s video Dream Soup depicts a shop that makes fake perfumes in the UAE, revelling in the saccharine beauty of the process of fakery.

Easternsports, by Alex de Corte and Jason Musson

The exhibition concludes with a number of works that seem to expand the idea of kitsch and its wider potential to remake the world. Slavs and Tartars offer a pickle-juice dispensing machine, an elaborate inside joke on contrasting global meanings and modes of presentation of consumer products between East and West. In the work of Alex de Corte and Jason Musson, Easternsports, we enter an immersive neon-shaded space, four walls arranged around a multicoloured carpet strewn with oranges, a self-contained ersatz world in which subtitled voices discuss culture the West has borrowed from the East.

Sinop calling: Hayırlı Evlat and friends let themselves go in Let Themselves Go

Finally, there is the video of Hayırlı Evlat’s faux-pop song Bırak Kendini (Let Yourself Go), a homage to the Black Sea city of Sinop, supposedly the friendliest in Turkey, projected on a loop. The artist has described his work as using happiness as a form of ‘soft resistance’. Through its calm, muted colours and playful use of form, the work is at once uplifting and infectious.

In his essay 1989 essay, ‘The Structure of Bad Taste’, Umberto Eco writes that kitsch represents ‘the systematic attempt to escape from daily reality’. Perhaps this is why it feels impossible to leave this exhibition without feeling elated and joyful, as if one is in on an inside joke; the Pera Museum itself seems transformed, somehow, into a strange Wunderkammer of the absurdity of life. Reframing our perception of kitsch, A Question of Taste offers a dramatic, and surprising, escape into another world – one of synthetic beauty, one that feels as liberating as it does strange.

_Pera_Museum_School_of_Fluid_Measures_Judith_Seng_420_408_80_c1.jpg)