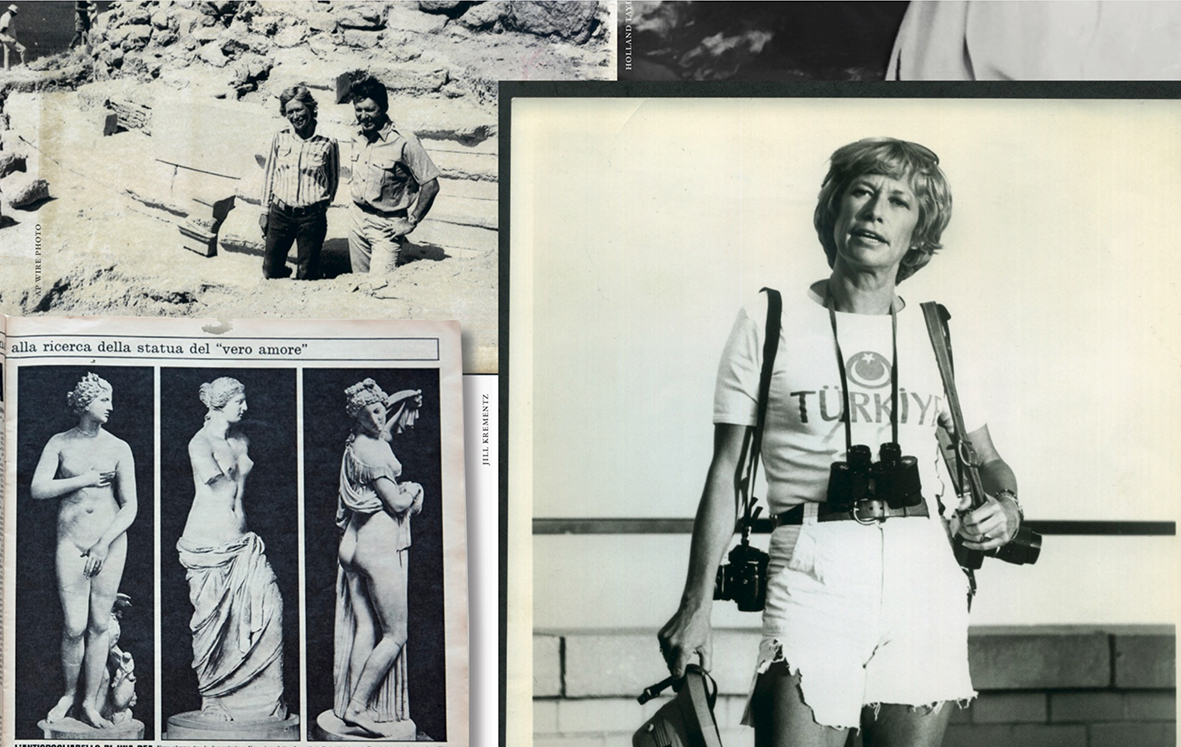

On July 21, 1969, in her mid-30s, Iris Love (photographed above by Michael Chesser) made the discovery that would see her become, for a short time, perhaps the most famous archaeologist in the world.

She was in her third season of excavations at Cnidus, in the extreme southwest of Turkey On that scorching day the excavations had been brought to a temporary halt by news from the Apollo 11 moon mission. While her team of volunteers listened to the radio, Iris decided to climb the ridge to the north of the site. Looking down from this ridge, she saw unusual outlines in the land on a small plateau overlooking the city. The next day she shifted the excavation there and immediately found the stepped base of a circular building. She became convinced, and began to build persuasive arguments, that this was nothing less than the temple that once housed Praxiteles’s statue of Venus Aphrodite, perhaps the most famous statue of the ancient world and one of Pliny’s Seven Wonders. If her thesis was correct, this was one of the greatest archaeological coups of the century.

The acropolis at Cnidus, a city blessed with two natural harbours and home to the Aphrodite of Praxiteles, one of Pliny's Seven Wonders (photo Michael Chesser)

The acropolis at Cnidus, a city blessed with two natural harbours and home to the Aphrodite of Praxiteles, one of Pliny's Seven Wonders (photo Michael Chesser)

She announced her discovery at a stunned annual conference of the American Institute of Archaeologists in San Francisco in the last days of 1969. It briefly became world news, and propelled Iris Love to the kind of fame archaeologists can only dream about. While her discovery appeared sensational, it was the glamorous young archaeologist herself – tall, blonde, handsome, self-confident and well-connected – that really caught the imagination of the world.

Iris Love seemed something new and glamorous in the fusty, male-dominated world of archaeology. She found herself on the front page of The New York Times (bronzed and in the skimpiest of minidresses), on prime-time national television being interviewed by Barbara Walters, and the subject of profiles in scores of magazines and newspapers around the world. Tabloids ran headlines such as ‘Love Finds Temple of Love’ and referred to her as ‘the mini-skirted archaeologist’.

It was at this point, in the first months of 1970, that Iris Love reached the zenith of her reputation. Among the academic compliments was an invitation to give the Annual Lecture at the Smithsonian Institution, a great honour for a young archaeologist. Offers to fund further digs at Cnidus poured in. There was a bulging mailbag, with requests for interviews and college talks.The Smithsonian and CBS agreed to collaborate on a one-hour Smithsonian Adventure, Search for the Goddess of Love (which was broadcast nationally in June the following year). She seemed set for a brilliant career in her chosen field, but events were about to take an unexpected turn that would make her more famous still – and do great damage to her academic standing.

In May 1970, on a visit to London en route to Turkey, there began a dispute with the British Museum from which Iris Love’s reputation never fully recovered. She had requested to see various unexhibited items from Cnidus in the Museum’s reserve collection. Amongst this collection was a 4th-century BC female head, much damaged, that Charles Newton had found in the Temple of Demeter, about half a mile from the Aphrodite temple. Newton (and virtually every scholar who had looked at the head since its discovery) had thought it to be of Persephone. Iris, gripped by a gut instinct, decided that this was nothing less than the head of Praxiteles’s Aphrodite – a wildly ambitious attribution for which there was scant evidence.

For the next few months Love sparred publicly with the BM. Initially the publicity was hostile to the museum and favourable to Iris Love. But slowly, as 1971 progressed, the tone of the coverage changed. Attention of a less flattering kind began to fall on Iris Love herself. A devastating profile in The New York Times Magazine of May 1971 (‘An Archaeological Find Named Iris Love’ by Elizabeth Stevens) describes her as impulsive, vain and a deliberate

seeker of celebrity. It also points out a critical weakness in her academic qualifications – she had no PhD. Iris responded with an irate letter to the magazine, calling the article ‘unworthy of The New York Times’, but she never managed entirely to live down the criticisms.

From this point the promising wunderkind of archaeology would increasingly be known as the profession’s eccentric. Although her excavations at Cnidus continued until 1977, her academic reputation would never fully recover.

Born in 1933, Iris Love was the child of well-off parents who were discriminating collectors of art. She had shown an early interest in archaeology and on graduating from Smith College, she worked as an assistant professor at Cooper Union. For nine summers, from 1955 to 1963, she worked as an assistant on that university’s summer dig in Samothrace in the northern Aegean. In 1966, while working as an assistant professor at Long Island University, she determined to mount her own archaeological excavation at Cnidus. She visited the site that summer by boat and was inspired by its location and its potential. There had been no excavations there since Charles Newton’s expedition from the British Museum had departed in 1859. It is a vast, remote and almost waterless site that posed considerable logistical challenges. Undaunted, Iris visited the Ministry of Antiquities in Ankara, requesting permission to excavate. This was granted, with the normal proviso that a supervisor (komiser) would be attached to the expedition.

Nowadays it is almost impossible to imagine how a relatively inexperienced archaeologist still only in her early 30s could have obtained permission to excavate such a major site. But things were different in the 1960s. More than 50 archaeological digs from US universities were taking place in Turkey at the time. The spirit of international archaeological cooperation was strong, and nowhere stronger than between Turkey and the United States.

Back at Long Island University, Iris raised $50,000 from various charitable trusts and friends of the family to fund the first year’s campaign. In Turkey the following summer she hired 100 men, paying $1 a day, and put together a team of young international archaeological assistants, about 25 in total. Everyone slept under canvas. Iris bought a Land Rover, in which she would bring drinking water and fresh vegetables to the site from Yazıköy, the closest village. Staple foods were tinned meat and bottled gherkins. Conditions were tough. Work began promptly with roll call at 7am. Lunch was from 12 to 3, then work resumed through the baking-hot afternoons. Organising and controlling the operation seemed to come naturally to Iris. The villagers of Yazıköy, unused to seeing a young woman in a position of authority, called her Müdür Bey, or Mr Director. The first two summers, in 1967 and 1968, were largely spent surveying the huge site, excavating the streets west of the Upper Theatre, the Necropolis and the Stoa, which Iris published in the American Journal of Archaeology. However, it was in her third summer that she made the sensational discovery of the Round Temple.

Excavations continued for 11 years at Cnidus, in part owing to Iris’s flair and energy for raising funds. Politically, things became more difficult following the Cyprus conflict in 1974, when she was once held at gunpoint in the office of the Kaymakam, the provincial governor. In 1975 the annual permit to excavate was granted only in August, and permits were obtained only with some difficulty for the following years. The final campaign was in 1977. There were also rumours, much exaggerated, of unprofessional methods on site.

Iris Love’s involvement with archaeology did not end with her departure from Cnidus. She held teaching positions at Long Island University and at Smith and was involved in excavations in China, but her attentions seem to have been increasingly claimed by the breeding of dachshunds and by a colourful social life in New York (she is mentioned no fewer than nine times in The Andy Warhol Diaries). Her annual Christmas party became famous. Although she passed the oral examinations for her doctorate with highest honors, she never finished her dissertation and so did not complete her PhD.

Scholars are divided about the Round Temple that she discovered. There are many things that seem to support her attribution – a circular temple seems to fit the description of the building in Pliny, and the circular building she discovered is almost identical in size to the Temple of Venus in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. But above all it is the building’s position that seems so suggestive of its purpose. To quote from Iris’s description in the AJA: ‘The temple is located on the highest, most western terrace of the city, a suitable location for the goddess of the evening star and a spectacular site close to and overlooking both the commercial and trireme harbours, whose ships Aphrodite Euploia protected.’

Most archaeologists, however, appear sceptical. Work at the site in recent years by Dr Ramazan Özgan from the University of Selçuk has shown it to be a second-century BC tholos with an outer Corinthian colonnade and an inner walled room, or cella. Moreover, it was dedicated not to Aphrodite, but to Athena. Dr Ian Jenkins, today’s curator of Greek sculpture at the British Museum, who has himself excavated at Cnidus, feels it is impossible to take any definitive view on its attribution. ‘It could be a Temple of Aphrodite and is certainly of near-identical proportions to the Temple of Venus at Hadrian’s Villa, but my feeling is that this temple was most likely a shrine to several gods, not to Venus Aphrodite alone.’ He feels that Iris Love’s work at Cnidus was ‘responsible and generally professional’. But he also feels that her relationship with Cnidus became ‘over-personalised’. He says ‘she became determined to discover the Goddess of Love and obsessed by the connection of her own name to that of Aphrodite’.

Visiting Cnidus today, Iris Love’s work seems deliberately downplayed and even unacknowledged. The interpretive board beside the temple she discovered reads: ‘The Round Temple Terrace, Second Century AD’. There is no mention of either Iris Love or Aphrodite. The official reaction to her death was equally tepid. A spokesman for Datca Belediye (Municipality) was quoted in Hurriyet newspaper as saying ‘we know little about her’, which seems disappointing when she dedicated so many years and so much energy to excavating at Cnidus.

Iris Cornelia Love was born in 1933 in New York. She died on April 17 in New York, having contracted COVID 19. She was 86.

Also see 'The Summer of Love', Cornucopia No 57, by Rupert Scott, with a portrait by Jürgen Frank. Available in the digital edition of Cornucopia (subscribers register here).