Mélodies: Debussy in Pamphylia, Fauré in Isfahan, Reynaldo Hahn in Istanbul. This new series of blogs is designed to provide a welcome distraction from for those in isolation, while at the same time introducing them to music that may be new to them and will give them pleasure. It is centred around writers of mélodies – French art songs – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

I have to say straight off that in reality Debussy never went to Pamphylia, and nor did Fauré go to Isfahan: they just wrote songs about these places. But Reynaldo Hahn really did come to Istanbul in the spring of 1906, and wrote a piece while being rowed over the Bosphorus in a caïque.

Who was Reynaldo Hahn then? Born in Caracas, Venezuela on August 9, 1874 (hello, Mr Leo!) to a Venezuelan mother of Basque origin and a father of German-Jewish extraction, he was the youngest of 12 children. When he was three, the family moved to Paris (one wonders how many taxis they needed to get from the railway station to the ship). Reynaldo, a child prodigy with a fine singing voice, he made his début at the salon of Napoleon’s eccentric niece Princess Mathilde, accompanying himself on the piano as he sang arias. At the age of eight he began composing his own songs, and four years later was permitted to enter the Paris Conservatoire, where his mentors included Jules Massenet (his first composition teacher), Charles Gounod and Camille Saint-Saens.

One of his songs, written in 1888 (when he was 13), was an instant success. It was a setting of a poem by Victor Hugo entitled Si mes vers avaient des ailes (‘If my verses had wings’), and was published by the French newspaper Le Figaro. The composer’s Wikipedia entry notes: ‘Many of the hallmarks of Hahn's music are already evident in Si mes vers: the undulating piano accompaniment, the vocal line derived from the patterns and intimacy of speech, the surprising intervals and cadences, the cleverly placed mezza voce, and the sophistication and depth of feeling.’

Here is a rendition of the song by the Dutch soprano Elly Ameling (1933–); she is accompanied by Dalton Baldwin.

In this series of blogs, I am going to list alternative performances of every work for which alternatives are available and of sufficient quality. I am assuming you will have ample leisure to listen to them, compare them and draw your own conclusions. If you do not wish to do this, however, you can of course skip the alternative performances, or cherry-pick among them.

So to start with, here are two renditions of Si mes vers avaient des ailes. The first is by the Texan mezzo-soprano Susan Graham, accompanied by Roger Vignoles:

Hahn’s songs often follow a strictly traditional form in which repetitions of the main theme are interspersed with episodes. He believed that ‘only form can give a piece a chance of lasting’. As evidence of this approach, Palmer quotes the three songs L’automne, Le printemps and Quand je fus pris au pavillon – ‘When I was lured to her pavilion’. (At this point, I have an apology to make to speakers of French: Spellcheck keeps changing ‘pavillon’ to ‘pavilion’, and in spite of my assiduous rearguard actions, by the time the current piece reaches publication this and other French words may well have been mangled by the orthographic obersturmbannführer.)

Here is Le printemps sung by the Texan mezzo-soprano Susan Graham with Roger Vignoles on the piano:

Now, the same work sung by the French operatic soprano Véronique Gens, accompanied by Susan Manoff:

You may be wondering why I always name the accompanist as well as the singer. There are two reasons for this: firstly, I have done a fair bit of accompanying myself, and secondly (to be more objective), the accompaniment does make a difference. In 1972 I had the privilege of listening to a talk by the distinguished British pianist Gerald Moore (1899–1987), author of The Unashamed Accompanist. His Wikipedia entry contains the following paragraph:

Moore is credited with doing much to raise the status of accompanist from a subservient role to that of an equal artistic partner. It is debatable whether he succeeded in convincing the British Establishment of his time of the uplifted status of his art. Whereas prominent conductors and singers, for example, in the British musical theatre were awarded knighthoods, he received a CBE, a lower-ranked award. Dietrich Fischer-Diskau wrote in his introduction to the German edition of The Unashamed Accompanist, 'There is no more of that pale shadow at the keyboard; he is always an equal with his partner’. Moore valiantly protected this status of his art, complaining when accompanists he admired were not given billing in concert.

But to return to our main theme, Hahn’s formalism is evident in what is probably his most famous song, A Chloris. The repeated ‘turns’ (in common parlance, the twiddles) over a descending bass in the accompaniment are a masterpiece of polished pseudo-baroque, while the modulations first to B major (the dominant key) and then to G sharp minor are managed in a way that Handel would undoubtedly have approved of. The bass line is, of course, a straight crib from Bach, but we will let that pass. The first performance I will list, by Susan Graham and Roger Vignoles, gives you the score:

And now, a live performance by the part-French, part-Italian mezzo-soprano Léa Desandre, accompanied by Sarah Ristorcelli:

Below is a link to the Oxford Lieder website, where you will find not only the French texts of many of Hahn’s songs (including A Chloris), but also English translations of them by Richard Stokes. On the ‘Featured Composers’ page, you need to click on ‘H’ for ‘Hahn’ in the alphabet menu at the top – Reynaldo is the first composer whose photograph appears when you get to ‘Composers by Name’. Click on his photograph, then on ‘Song List’.

All these songs can, of course, be sung by male singers as well as female. Here is a performance by the counter-tenor Philippe Jaroussky, the owner of a truly amazing voice. It is difficult to believe that Jaroussky graduated from the Paris Conservatoire not as a singer, but as a violinist. It was only later that he took up vocal training. On this occasion, his accompanist is David Kadouch:

I note that another YouTube video of Jaroussky performing this song (as part of an album entitled Opium) does not name the accompanist. Accordingly, I have passed it up – in protest at the omission. In this next video he is singing Hahn’s L’heure exquise, accompanied on the piano by Jérôme Ducros. Jaroussky’s top F sharps admittedly veer towards G on occasions – that last one is definitely off-key – but even so I like to see the singer enjoying what he is doing:

Now, back to lady singers: in this rendition of L’heure exquise, the Swedish mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter is accompanied by Bengt Forsberg. I greatly admire her breath control in that last phrase. She is a Taurus, I see – guess which sign rules the throat?

Before moving on to describe Hahn’s visit to Istanbul and his later career, I would like to present his song Le rossignol des lilas – ‘The Nightingale of the Lilacs’. I do not know exactly when it was composed (one source gives the date of publication as 1896), but the piano part shows signs of a mature style. In the first of these two videos, Véronique Gens is accompanied on the piano by Susan Manoff, while in the second the performers are Susan Graham and Roger Vignoles:

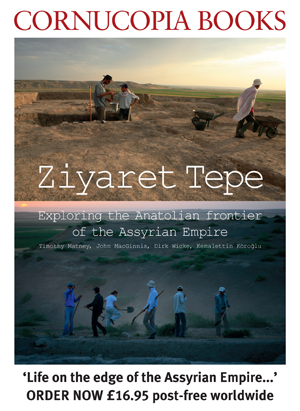

As I said in my article on Hahn’s visit (see the December 2014 issue of Andante), after returning from Istanbul he composed a number of piano pieces that were later published in the second volume of an album entitled Le rossignol éperdu (‘The Distraught Nightingale’) – in a section of this album entitled Orient. These pieces are En caïque, Narghilé, Les chiens de Galata and Rêverie nocturne sur le Bosphore. At the end of Rêverie nocturne, we see the following inscription: ‘Ecrit en caïque au clair de lune, 1906’ (‘Written in a caïque in the moonlight, 1906’).

During his researches at the Galata SALT archive, where there are digital scans of newspapers held at the Atatürk Library in Taksim, Dr Aracı turned up an article on Hahn’s visit to Istanbul in a Levantine newspaper. Published in French as Le Moniteur Oriental, this newspaper also had some pages in English (these appeared under the name The Oriental Advertiser); however, the relevant article, which was published in the issue dated 2 May 1906, was available only in French. A translation follows below.

(Illustration courtesy of Dr Emre Aracı/SALT Galata)

M. Raynaldo [sic] Hahn has been here for several days now.

What musical dilettante with something of a voice has not hummed the Chansons grises of this composer, who was a pupil of Monsieur Massenet and is a product of his tuition?

M. Raynaldo Hahn, who has been living in Paris for many years, is Venezuelan by birth. After completing a serious course of study under M. Massenet’s direction, he began producing songs of great tenderness which soon won the enthusiastic approbation of music-lovers. The appearance of [new] works by him is awaited with eager anticipation.

But his output has not been limited to this [i.e., to songs]: M. Raynaldo Hahn has also ventured into the realm of theatrical production, and not without success. Not long ago, a musical comedy of his entitled 'La Carmélite' was staged at the Opéra-Comique; this sound, well-constructed work revealed that its creator possesses qualities of substance.

M. Raynaldo Hahn will be staying in Constantinople for a few days more; he is passing through as a simple tourist. May the Orient inspire him to create a new work shot through and through with his languid mellowness!

The trip to Istanbul did indeed produce a new work ‘shot through and through with his languid mellowness’: entitled Rêverie nocturne sur le Bosphore, it was later published in the album of piano pieces mentioned by Dr Aracı Le rossignol éperdu. It is being played here by Laure Favre-Kahn:

If Reynaldo did indeed write this ‘in a caïque in the moonlight’, one cannot help wondering how he managed to hold the manuscript paper steady as the boat rocked to and fro. But I would imagine that in reality, he just jotted something down when he was back on dry land, and wrote it out in full on his return to Paris.

Now, here is Michael Finnissy playing Narghilé, another of the pieces in this album that have something of an Istanbul flavour to them. In this one, the composer adds some major chords to the mostly minor mix:

In the extract from Le Moniteur Oriental reproduced above, reference is made to Hahn’s musical comedy La Carmélite. This was not his first effort in the operatic field: by 1906 he had already written L’île du rêve (‘The Dream Island’), which was produced at the Opéra-Comique in 1898. His biggest hit, however, came with an operetta entitled Ciboulette (‘Chives’) that won instant acclaim when first performed in 1923. Hahn also composed ballet music: Le Dieu bleu (‘The Blue God’) was written in 1912 for Sergei Diaghilev’s company to a scenario by Jean Cocteau and Federico de Madrazo y Ochoa.

Reynaldo Hahn was a conductor as well as a composer: in the 1920s and 1930s he was general manager of the Cannes opera house. He was also an influential music critic, working for Le Figaro – the newspaper that had published his youthful composition Si mes vers avaient des ailes.

Hahn left Paris in 1940, during the German occupation. In 1945 he returned to become director of the Paris Opera, but his days there were unfortunately numbered: he died of a brain tumour in 1947.

As a parting bouquet, here is a performance of his six-song Venezia cycle performed by the American lyric-coloratura mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato with David Zobel on the piano. The introductory talk by Ms DiDonato is great fun – it seems Hahn’s adventures in the field of waterborne music went a long way beyond his Istanbul exploit: